By Briana Pocratsky

On a warm, sunny Saturday evening I walk down R Street NE toward the Metropolitan Branch Trail. A train rumbles past on Metro’s Red Line. I look to my left. A red brick warehouse, Penn Center, sits on the outskirts of Eckington, an industrial neighborhood in Northeast Washington, D.C. On the side that faces the rail line is a large mural of black, white, and gray that runs the length of the building. Emerging from the brick surface are images of the Lincoln statue, people quarrying large blocks of marble, and a man chiseling. This mural, “28 Blocks,” has received substantial local media coverage and interest the past few weeks.

“28 Blocks”

The mural includes a familiar sight: the Lincoln Memorial statue, which sits a few miles southwest. Since its official unveiling in 1922, this marble statue of the 16th President has been a witness to a range of important historical events. The popular narrative surrounding the creation of the Lincoln statue typically credits architect Henry Bacon and sculptor Daniel Chester French with designing the Lincoln Memorial and the Lincoln statue respectively; but, there’s more to the story. “28 Blocks” provides a more complete visual account of the statute’s creation. The mural highlights the often overlooked contributions of individuals whose labor made not only the statue but the nation possible. Referring to the twenty-eight blocks of white Georgia marble used for the statue’s construction, the title suggests that this mural has a different story to tell.

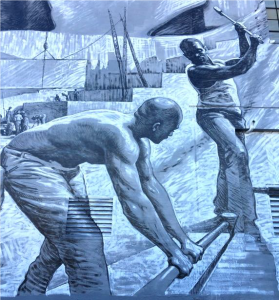

While the mural includes a rendering of the familiar Lincoln statue at its far end, there are a number of less familiar images that accompany Lincoln as one walks down the Metro trail. In the trailer for the “28 Blocks” documentary film, the mural’s artist Garin Baker explains that “28 Blocks” started with the question of who built the Lincoln Memorial statue. Looking into the history of the statue, Baker found that first and second generation freemen and Italian immigrants were integral to the iconic statue’s construction. A quote by Frederick Douglass at the bottom left of the mural reminds us that finished products or end results have a history that precede them. The inclusion of the quote within the context of the mural suggests that without the labor that went into the statue there could be no great statue –with every end product there are very important, and often unrecognized, means.

While the mural features Daniel Chester French thoughtfully examining a small scale model of the statue, the mural also features less well-known creators of the statue and its setting. Also referenced in the mural are African American men, who quarried the marble used for the statue; Evelyn Beatrice Longman, a woman sculptor who created decorative art that is inside of the Lincoln Memorial; and the Piccirilli Brothers, a family of Italian immigrants who carved the statue.

The Complexities of Public Art

As I sit on a bench near “28 Blocks,” I see people on the trail pause at the mural. One cyclist stops, looks at Frederick Douglass’ quote for a while, and takes a selfie with the mural. Others on the trail glance at the mural for a few moments as they walk, jog, or bike past. A few others simply pass by, unfazed by, or perhaps already familiar with, the huge mural. While “28 Blocks” seems to be welcome in Eckington and in the District, public art is not always welcome in its intended spaces.

The seemingly positive reception of “28 Blocks” by the general public led to me think about public art, mainly its definition and its relationship to society. The notion of art itself is a topic that can result in a number of questions. What is art? Does art have a role in society? Can art be revolutionary? The notion of public adds yet another layer of complexity to an already challenging topic. For example, is “public art” art made by the public, art presented in a public space, or art made for the public? Whatever the case, public art is related to public opinion in some way, especially when the artwork is tied to public space and public funds.

In the 1990s, two artists, Vitaly Komar and Alex Melamid, attempted to understand the world’s Most Wanted paintings and surveyed individuals in a number of countries for their aesthetic preferences in order to “discover what a true ‘people’s’ art would look like” (Dia Art Foundation 2016:1). Based on the survey results, the artists created a painting for each country that reflected these preferences.

The U.S.’s Most Wanted painting is the size of a dishwasher and features a hodgepodge of images including George Washington, children, and wild animals (a hippo and deer) in a grassy green foreground with blue water, mountains, and sky in the background. The project as a whole is tongue-in-cheek; a commentary on the reliance and inadequacy of polling as a means of participatory democracy and the reduction of everything to numbers in general.

The project also demonstrates the difficulties in incorporating numerous opinions into a singular whole or, in this case, a work of art. Most Wanted illustrates how public opinion may be distorted or misrepresented and gets at some of the complexities of a democratic society.

The following example shows how public art can result in controversy if power and authority are concentrated outside of the public, such as with the artist or the government. Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc, a 12’ X 120’ X 2 ½’’ modernist COR-TEN steel sculpture, was a site-specific public artwork installed in 1981 in Federal Plaza, Manhattan. Commissioned by the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA), Tilted Arc sat in a busy plaza surrounded by federal office buildings.

Serra’s sculpture caused controversy and illuminated societal tensions about private/public spaces and power, illustrated by petitions, a public hearing, a lawsuit, and media coverage. Some found Serra’s work to be an obtrusive, elitist eyesore and even a potential safety hazard that dismissed local culture. Others found it to be purposely disruptive and critical artwork that did not pander to the public. Removal of Tilted Arc from Federal Plaza would destroy Serra’s site-specific public art.

Tilted Arc highlights the lack of public spaces dedicated to fostering debate. As historian Casey Nelson Blake (1993:250) explains, Tilted Arc “demonstrates that the most important source of the aesthetic crisis of public art is the ongoing political crisis of the public sphere. Bitter disputes of the aesthetic and social functions of public spaces both reflect and contribute to a waning belief in the very possibility of a democratic public sphere constituted by collective deliberation.” As sociologist Steven C. Dubin (1992:38) further explains, public art controversies tend to occur when “there is a high degree of communal fragmentation and polarization, and widespread civic malaise and low communal morale.” This controversy usually manifests at public sites, such as Federal Plaza. Eight years after its installation the federal government removed Tilted Arc from the plaza, replacing the artwork with benches and some landscaping.

Public Art: Always Controversial?

When public art causes major controversy, it becomes clear that art, especially public art, can materialize complex power dynamics that were hidden, dormant, or largely unchallenged. But, public art does not have to be controversial to provide a commentary on power or to enrich a community or public. This is evident by the reception of Baker’s mural. “28 Blocks” is not Baker’s first work of public art; Baker is well-known for “public art murals” across the nation and in Europe. Rooted in realism, Baker’s murals are approachable, welcoming passerby to linger on details of large-scale art.

While Baker’s mural may disrupt our notion of the narrative surrounding the Lincoln statue, the mural also promotes a needed narrative of solidarity in a particularly divisive time in U.S. history. By using an iconic image woven into the cultural fabric of the nation, Baker grabs the public’s attention in order to convey a narrative that would otherwise be unknown or dismissed.

Celebrating the contributions made by immigrants and African Americans to the construction of this national symbol, the mural challenges and complicates the dominant narrative of who helped to build the nation. To view Garin Baker’s public art murals and other artwork, visit http://garinbaker.com/.

References

Blake, Casey Nelson. 1993. “An Atmosphere of Effrontery: Richard Serra, Tilted Arc, and the Crisis of Public Art.” Pp. 247-289 in The Power of Culture: Critical Essays in American History, edited by R.W. Fox and T.J.J. Lears. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Dia Art Foundation. 2016.

“Komar + Melamid: The Most Wanted Paintings.” Retrieved September 8, 2017 from (https://www.diaart.org/program/exhibitions-projects/komar-melamid-the-most-wanted-paintings-web-project).

Dubin, Steven C. 1992. Arresting Images: Impolitic Art and Uncivil Actions. London: Routledge. National Park Service. 2017.

“Lincoln Memorial Builders.” Retrieved September 3, 1027 from (https://www.nps.gov/linc/learn/historyculture/lincoln-memorial-design-individuals.htm).

Strong, Shawn. 2017. “28 Blocks Trailer.” Vimeo website. Retrieved September 2, 2017 from (https://vimeo.com/222625398).

Thank you Briana, for your thoughtful article about my “28 Blocks” Mural. I just recently stumbled upon it and was taken by your thorough examination of it’s relevance to public art in general and the specific narrative I was attempting to convey. Yes, I was trying to lay blame for the creation of this symbolic and iconic monument that is heralded by so many as a prominent pillar of America. But for many the truth is marred by one’s point of view and the truth of the real history is often lost in time. Who did build it and symbolically who has truly built this nation? Of late there is a lot of public discussion about where one come from and who are truly Americans. For s long time we hear about the titans of industry and the fathers of our country but when one looks a bit deeper we find the truth about who actually did the real work towards laying the cornerstones and foundations of building “American Greatness” are the names of the faceless and heroism of the working men and women that have been sacrificed by history. It was my sincere hope to herald this in the hopes to encourage a discussion that looks deeper for the beauty in truth that we can all take pride in.