By Brandi Thompson Summers

What are we to make of this image of a clinched raised fist? An image that resonates with a distinct global history; an image that the brewery’s owners said derives from their desire to represent Washington, D.C. as a neighborhood and not merely the nation’s capital.

For those familiar with the D.C. flag, this logo directly references the emblematic “stars and bars.” But the clinched fist is widely recognized as a radical leftist symbol of solidarity, defiance, unity, and most notably resistance among oppressed people. While the redness of the fist might lead us to consider its relationship to the “red salute”— a symbolic marker of power and solidarity amongst communists and socialists — its association with D.C., the first Chocolate City, invokes us to see the fist as a nod to the black freedom movement tradition.

It conjures memories of the black power salute, of John Carlos and Tommie Smith raising their fists in Mexico City, of power to the people.

In the Chocolate City Beer logo, blackness is defined as edgy and cool, creative, resistant, unruly, and commercial. The absence of an actual black fist allows the red fist to operate in aesthetic proximity to blackness. While the red fist asks us to imagine its symbolic universality, the image need not be black in order to evoke blackness.

As an aesthetic, blackness no longer relies on the presence of black people, or in this case black limbs for social traction. Aesthetics define blackness in particular ways and open up space for play with the fluidity and instability of blackness especially when black bodies are not present.

Reimagining H Street

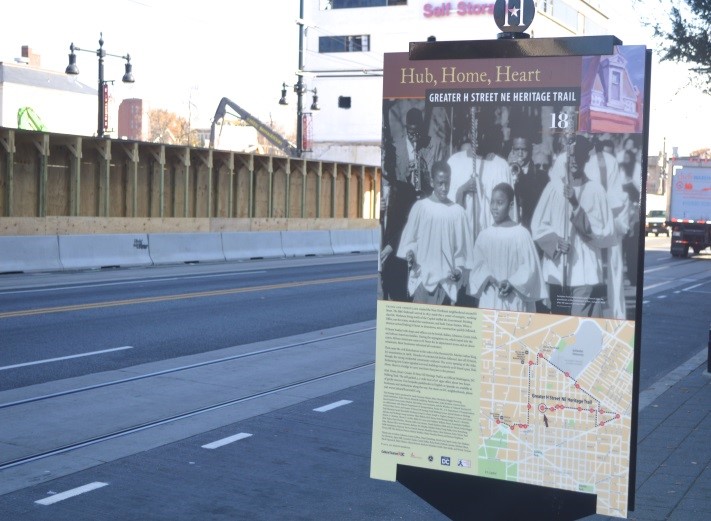

I use this piece to think about how blackness structures the design and execution of rebuilding and reimagining the H Street, NE corridor — a Washington, D.C. neighborhood in transition. As D.C. undergoes demographic change, I want to focus our attention on how the built environment informs how we think about racial aesthetics.

What is interesting about a place like D.C. is that it is not only recognized as “chocolate” because of the bodies that inhabit it, but because of its juxtaposition with a power structure steeped in white privilege (white politicians, white residents). In other words, D.C. is black and Washington is white.

The Chocolate City label originally referred to Washington, D.C., but Parliament’s 1975 song of the same name opened up the designation to include cities like Newark, Gary, and Los Angeles where blacks became the majority population as white residents fled to the suburbs.

But as I noted at the outset, the concept of “Chocolate City” is linked to the political and cultural imaginations of the civil rights and black power eras. The Chocolate City of the funk era referenced an aesthetic of black empowerment and nationalism in music, fashion, politics, and the visual arts.

In contrast, the current post-Chocolate City aesthetic markets a depoliticized black cool in the multicultural, neoliberal city — a dynamic the Chocolate City Beer insignia captures all too well. Where diversity was once invoked to emphasize the need for federal programs that enhanced the life chances of an entire demographic, the concept of diversity is now frequently used to emphasize opportunities for individuals to accrue cherished commodities and individual advantages.

Diversity is Cool

The consequence of this widespread shift in the value of diversity is that people can associate themselves with the nobility that derives from the term’s social justice origins, while partaking in its more recent iterations of what it means to be “cool” and “hip.” In the context of diversity’s shift from a social justice ethic to an aesthetic lifestyle amenity, blackness enhances rather than threatens the esteem of a given neighborhood (Modan 2012).

District government agencies, private developers, historic preservationists, and others work together to provide official representations of a past that existed before H Street was “chocolate,” as a way to promote and develop the space.

The production of an official history attracts visitors and justifies the deployment of diversity as a construct that might not deter white residents and patrons. Diversity becomes a cherished asset. Overall, I highlight a shift away from black enterprise and aesthetics on H Street to think about the ways that governing, markets, space, and style are now organized around diversity.

This matters because the narratives are about the diversity of the H Street corridor, how bodies move through this space, what places and people are cool, safe or unsafe, and the kinds of establishments where the bodies belong.

From H Street to Great Street

Recognized as one of three commercial districts devastated by riots following the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the H Street, NE corridor was named USA Today’s top “up and coming” neighborhood as well as one of Forbes magazine’s “Hippest Hipster” destinations in 2011. The history of H Street tells the story of a black space that underwent significant challenges to achieve the political and economic infrastructure that enabled it to thrive.

The area did not suffer from lack of attention or a commitment of funds, but a lack of sustainable options to support the people who lived, worked and shopped there.

In the years following the 1968 riots, the H Street, NE corridor was deemed, particularly in the media as blighted, unwelcoming, and teeming with transient people who did not care about their own condition or the conditions of their environment. Although the downfall of the H Street corridor was due to several factors, negative renderings of blackness prevented the restoration of H Street as a renewed black retail space. Prior to the 1950s, the H Street, NE corridor provided numerous retail options, eateries, and public spaces to black residents that were central to economic and social life.

Back then, H Street was known as a sustainable black-business downtown district because segregation laws prevented black patrons from shopping at downtown D.C. businesses. Before the 1968 riots, it was the most significant commercial activity center within the greater Capital East area. The corridor was second only to downtown D.C. in the production of jobs and tax revenue.

By the 1960s, H Street suffered at the hands of suburbanization in America, when mostly white, middle class residents left the cities for the suburbs and used malls as their main shopping source. A combination of state and corporate divestment, abandonment, and disparaging representations of urban markets and black consumers left urban commercial corridors like H Street to falter.

Post-riot H Street underwent significant challenges in its rebuilding. Of the three riot corridors, none were so slow in redeveloping as H Street. As the neighborhood grew increasingly poorer and blacker, the closure of several key retail stores in the 30 years following the riots left large gaps in its streetscape.

Plans for the redevelopment of H Street in the late 1960s and 1970s originally included significant involvement and decision-making power in the hands of local groups led by black residents and community leaders. The rebuilding of H Street was seen as an opportunity for the black community to control the money, jobs, and political power.

Black residents living in the area wanted the corridor to be planned by black developers, built by black architects, and refreshed with local black-owned businesses, who they believed could meet the needs of the predominantly working-class black neighborhood (Kaiser 1968, The Washington Post 1968).

But plans to refurbish H Street as a black-developed and black-operated commercial corridor were later deemed economically impractical and unfeasible.1 It was not until the Williams administration in the early 2000s that changes took hold and H Street attracted a number of investors and developers to transform the neighborhood.

The Williams administration particularly stressed neoliberal development strategies that encouraged economic growth through the proliferation of public-private partnerships.

Rather than emphasize an expanded role for the local government, several of the programs introduced by the administration, like the Main Streets and Great Streets initiatives, largely supported entrepreneurial efforts towards the growth of small businesses. These initiatives limited the role of the local government in providing various services for its residents, in favor of free market approaches to economic development.

Judging by the content and dramatic increase in media attention, commercial development and capital to the corridor, current value of H Street is abstractly conceived through material and symbolic representations of diversity, “hipness” or ”coolness.” These discursive representations affect the resources the area receives.

Resources like policing, surveillance, national media attention, and visits by political figures and celebrities increase as the area is deemed more desirable. The importance of diversity and cultural consumption intensifies social and economic inequities by valorizing diversity in particular areas and making previously undesirable spaces popular.

Again, renewed energy around the development of H Street in the 2000s placed particular emphasis on the corridor as a welcoming space of diversity.

Diversity became a positive characteristic for business and tourism along H Street. National brands and local public-private partnership organizations strategically incorporated diversity as part of their official language to justify their introduction to the space — signaling affective cohesion with the neighborhood. For example, diversity is conceptually incorporated as part of the vision for H Street’s future in D.C.’s 2004 official strategic plan (D.C. Office of Planning 2004:32).

Similarly, marketing materials produced by the Washington, D.C. Economic Partnership (a public-private partnership that promotes business opportunities in D.C.) highlight cultural diversity as integral to the roots of H Street and its contemporary growth.

The introduction of retail businesses like Whole Foods Market, that serve an upper-middle class customer base, shows us the ways H Street has come to resemble other contemporary “revitalized” urban spaces.

Whole Foods uses diversity as a way to accrue value for both its brand and the H Street’s brand. A 2013 press release announcing the new store references the corridor’s diversity as an attribute and implies that communities with diverse, commodifiable cultural opportunities can benefit both old and new residents. So, in the case of H Street, the neighborhood is both seen and aesthetically valued by corporate interests as a diverse space.

The Corner: Racial Aesthetics and Politics of Belonging

The concept of diversity is not necessarily rooted in demographic representation, but in the visibility of racial difference. This is where we can point to blackness as a necessary component of diversity, as it indicates our successful transition into a post-racial social climate. Therefore black bodies must be there in order to make the space diverse.

In particular, the 8th Street and H Street intersection at the center of the corridor is an important site for the corralling of blackness and managing the excess of blackness in a specific location.

The intersection is now the city’s busiest bus transfer point, the number one bus transfer location in the District, and is a central gathering place for lower-middle class and working-class black city dwellers.

The corner served as an important junction from the early to mid-twentieth century when the streetcar was originally in service, which led to the commercial cluster that developed at the intersection of 8th and H Streets. This corner continues to be a center of activity and a meeting place along the corridor. But it has also had a particularly sordid history.

It was from this location that the “Eighth and H Street Crew” got its name. Sixteen members of the “crew” were charged with the 1984 slaying of 49-year old Catherine Fuller — often described as the most brutal murder in District history. Attempts to relieve this intersection from its reputation as the gathering place of the Eighth and H Street Crew came in the form of several plans for commercial redevelopment.

The H Street Connection shopping center that begins at the southeast corner of 8th and H Streets opened in 1987 and was heralded at that time as the centerpiece of redevelopment efforts on H Street.

Because the intersection is known for its high volume of black bus riders who travel across the river to Anacostia, blackness can be contained on this corner as the riders socialize and wait for their transit.

The corner is surrounded by several businesses including a corner store, athletic shoe store, a convenience store, McDonald’s, a Chinese food carryout, a liquor store, and a check cashing facility.

As the rest of corridor starts to cater to more affluent consumers, these black bodies are invited to stay not for long, to share the corridor only momentarily, spatially or economically.

The presence of black bodies congregating around 8th Street and H Street provides evidence of the corridor as a welcoming, inviting space for all, while maintaining a bit of edginess and perceived danger. Blackness serves to make claims on the success and durability of the post-racial.

Repurposing the Neighborhood

In the redevelopment of the H Street, NE commercial corridor, diversity is used to attract capital, customers, and tourists to the area. Diversity discourse makes blackness one of many inflections while H Street acts as a neoliberal zone that sustains reforms and affirms blackness by using it as an entrepreneurial machine of development.

It is through the work of diversity that H Street emerges as a hip, yet edgy, district. Nevertheless, while diversity evokes difference, it does not provide commitment to redistributive justice.

In light of H Street’s violent past, the narrative describing its history reinvents itself as multicultural in order to write the violent times away and repurpose the neighborhood for a new market and a new time. Racism and other forms of inequality that take place here are not overt, but subtle, and euphemisms like creativity, and cultural vibrancy can be used to disinvite.

Black excess can be unwieldy if not disciplined, managed, contained or deployed for proper use.

What happens as a result of H Street’s remaking is that the area hasn’t been purged of symbols of blackness; instead blackness is transformed to become palatable and consumable while some of its edginess remains.

I want to close by returning to the Chocolate City Beer insignia. Critics openly complained about the name of the company when it was discovered that the now defunct brewery was the brainchild of two white men who invited two black men to join the partnership. In response to this scrutiny, one of the white owners explained that the decision to use the clinched fist as their logo came from their desire to use “iconic images” rather than any direct reference to race or black political history (Kitsock 2011).

The “chocolate” in Chocolate City may no longer reference blackness as in the moment of integration, civil rights, and black nationalism, but instead refers to post-racial America, at a time when black aesthetics and diversity discourse can be deployed independently of black people.

Notes

- In fact, on May 10, 1968, one month after the riots, then City Council Chairman, John W. Hechinger released a statement rejecting plans for H Street, NE to be rebuilt expressly by black people. Hechinger, whose corporation later built the Hechinger Mall at the eastern edge of H Street in 1981, said plans to rebuild and run riot-torn areas promoted an “ideology of two separate societies,” therefore these ought to be rebuilt by all races.

Works Cited

- The Washington Post 1968. “Negro-Run Ghetto Mapped by Pride.”April 17, pp. A21.

- District of Columbia Office of Planning. 2004. Revival: The H Street NE Strategic Development Plan. Washington, DC: Government of the District of Columbia.

- Kaiser, Robert. 1968. “Burned Out in Riots, Many Owners Won’t Reopen.” The Washington Post, August 1, pp. H3.

- Kitsock, Greg. 2011. “Beer: Chocolate City Starts Small, Plans to Stay That Way.” The Washington Post, September 21, pp. E05

- Modan, Gabriella. 2008. “Mango Fufu Kimchi Yucca: The Depoliticization of ‘Diversity’ in Washington, D.C. Discourse.” City & Society 20(2):188-221.