By Ruth Milkman

The United States made substantial progress toward reducing gender inequality in the late twentieth century, not only thanks to the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s but also as an unintended consequence of the shift to a post-industrial economy. The gender gap in pay rates, for example, narrowed not only because unprecedented numbers of women gained entry to the elite professions and upper-level management starting in the 1970s, but also because real wages for male workers, especially those without a college education, fell sharply in that same period with de-industrialization and union decline.

As manufacturing withered, the traditionally female-employing service sector expanded; surging demand for female labor, in turn, drew more and more married women and mothers into the workforce. By the twentieth century’s end, women typically were employed outside the home throughout their adult lives, apart from brief interludes of full-time caregiving. They were far less likely to be economically dependent on men than their mothers and grandmothers had been. Their legal and social status had dramatically improved as well, and the idea that women and men should have equal opportunities in the labor market won wide acceptance.

Women workers continued to face serious problems, including sex discrimination in pay and promotions, sexual harassment, and the formidable challenges of balancing work and family commitments in a nation that famously lags behind its competitors in public provision for paid family leave and child care. Still, by any standard, the situation has improved greatly since the 1970s. This improvement has not been evenly distributed across the female population, however.

On the contrary, in precisely the same historical period during which gender inequalities declined dramatically — the 1970s through the early twenty-first century — class inequalities rapidly widened, with profound implications for women as well as men. Class inequalities among women are greater than ever before.

Highly educated, upper middle class women — a group that is vastly overrepresented in both media depictions of women at work and in the wider political discourse about gender inequality — have far better opportunities than their counterparts in earlier generations did. Yet their experience is a world apart from that of the much larger numbers of women workers who struggle to make ends meet in poorly-paid clerical, retail, restaurant, and hotel jobs; in hospitals and nursing homes; or as housekeepers, nannies, and home care workers.

Many of those working women are paid at or just above the legal minimum wage; and some — especially women of color and immigrants — earn even less because their employers routinely violate minimum wage, overtime, and other workplace laws. Although female managers and professionals typically work full time (or more than full-time), many women in lower-level jobs are offered fewer hours than they would prefer, a problem compounded by unpredictable work schedules that play havoc with their family responsibilities. Millions of women are trapped in female-dominated clerical and service jobs that offer few if any opportunities for advancement, and in which employment itself is increasingly precarious. For them, best-selling books like Sheryl Sandberg’s 2013 Lean In, which encourages women to be more assertive in the workplace, are of little relevance. Indeed if women in lower-level jobs are foolhardy enough to follow such advice, they are more likely to be fired than to win a promotion or pay raise.1

The widening inequalities between women in managerial and professional jobs and those employed at lower levels of the labor market are further exacerbated by class-differentiated marriage and family arrangements. Most people marry or partner with those of a similar class status, a longstanding phenomenon that anthropologists call class endogamy. This multiplies the effects of rising class inequality: at one end of the spectrum are households with two well-paid professionals or managers, while at the other end households depend on one (in the case of one-parent families) or two far lower incomes.

In addition, affluent, highly educated women are more likely to be married or in marriage-like relationships than are working-class women, and such relationships are typically more stable among the privileged. Women in managerial and professional jobs not only can more easily afford paid domestic help, but also are more likely to have access to paid sick days and paid parental leave than women in lower-level jobs. And families routinely reproduce class inequalities over the generations: affluent parents go to great lengths to ensure that their children — now daughters as well as sons — acquire the educational credentials that will secure them a privileged place in the labor market, similar to that of their parents, when they are grown.

But class divisions have widened over recent decades within communities of color as well as among women. Although to a much lesser extent than among white women, unprecedented numbers of women of color have joined the privileged strata that benefitted most from the reduction in gender inequality over recent decades. There is a literature on “the declining significance of race,” starting with William Julius Wilson’s 1980 book of that title.2 More recently, public concern about growing class inequality has surged. Yet the rapid rise in “within-group” class inequalities among women has attracted much less attention.

One dimension of this problem involves the recent emergence of class disparities in regard to the longstanding phenomenon of occupational segregation by gender, a longstanding linchpin of gender inequality and also the most important driver of gender disparities in earnings. (That is so because unequal pay for equal work, although still all too often present, is a smaller component of the overall gender gap in earnings than the fact that female-dominated jobs typically pay less than male-dominated jobs with comparable skill requirements.)

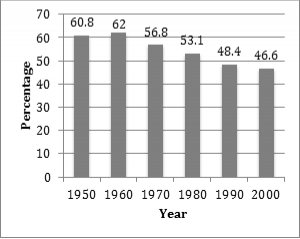

Whereas between 1900 and 1960, the extent of occupational segregation by sex was notoriously impervious to change,3 it began to decline substantially in the United States since 1960. The standard measure of segregation, “the index of dissimilarity,” which specifies the proportion of men or women who would have to change jobs to have both genders evenly distributed through the occupational structure, declined sharply between 1960 and 1990, and in later years continued to fall at a less rapid pace, as Figure 1 shows.4 This also led to a steady decline in the gender gap in earnings. Among full-time workers, women’s annual earnings were, on average, 59.94 percent of men’s in 1970; by 2010 the ratio had grown to 77.4 percent.5

Figure 1. Occupational Segregation by Gender, United States, 1950-2000

Note: Index of dissimilarity computed from U.S. decennial census data (IPUMS) Source: http://www.bsos.umd.edu/socy/vanneman/endofgr/ipumsoccseg.html

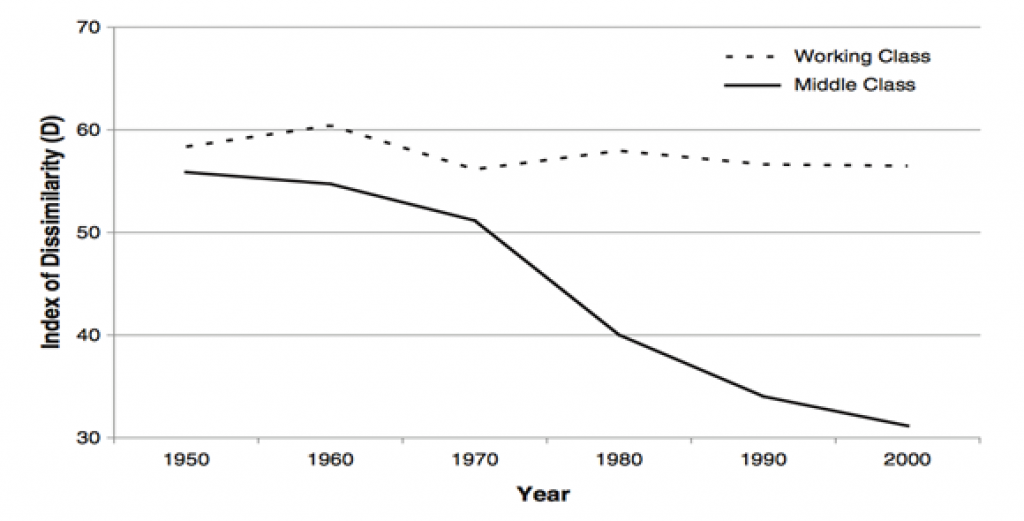

More specifically, occupational segregation by sex has declined sharply in professional and managerial jobs, but has hardly declined at all in lower-level occupations, as Figure 2 shows. High-wage “male” jobs in industries like construction and durable goods manufacturing remain extremely sex-segregated, as do low-wage “female” jobs like child care, domestic service, and clerical work.

Figure 2. Class Differences in Occupational Segregation by Gender, 1950-2000

Source: David A. Cotter, Joan M. Hermsen, and Reeve Vanneman, “Gender Inequality at Work,” The American People: U.S. Census 2000 (New York: Russell Sate Foundation and Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau, 2004)

College-educated women have disproportionately benefited from occupational integration, while less educated women are much more likely to be in traditionally sex-stereotyped jobs with low pay and status.7

As one would expect, college-educated and professional-managerial women also tend to earn substantially higher salaries than those women who remain ghettoized in poorly paid, highly segregated jobs at lower levels of the labor market. This is one of the reasons that income inequality among women has grown, even as the overall gender gap in pay has declined.

A similar pattern of inequality applies to benefits: women in professional and managerial positions are far more likely to have access to employer-provided health insurance, as well as paid sick days, and paid parental leave than women in lower-level jobs.8 And women in elite fields are also disproportionately likely to be able to purchase paid domestic help and other services to replace their own unpaid labor inside the home.

But the class pattern of gender disparities in earnings in the late twentieth century is complicated. In absolute terms, highly educated women in elite occupations have been able to advance economically to a much greater extent than women in lower-level jobs.

However, the relative decline in earnings inequality by gender was actually smaller for women at the upper levels – simply because the earnings of men in elite jobs rose far more rapidly than the earnings of any other group.

Indeed non-college-educated men have experienced a steady and steep decline in real earnings since the 1970s, a key factor contributing to the narrowing of the overall gender gap in pay.9 Further complicating the picture is that women in high-level managerial and professional jobs are required to work longer hours than women in most lower-level jobs; and if they are parents, they also face the time demands of “intensive mothering,” aimed at ensuring that their children obtain elite educational credentials and reproduce their class status.10

The surge in economic inequality since the 1970s has been greatly amplified by endogamous marriage and “assortative mating” – that is, the longstanding tendency for people to choose partners and spouses from class (and racial) backgrounds similar to their own. This pattern disproportionately benefits highly educated women in elite occupations who share a household with a male spouse or partner at a similar occupational level. Those women, even if they earn substantially less than their spouses or partners, indirectly benefit from the soaring incomes of those men — as well as from their wealth, which is distributed far more unequally than income. Indeed, income homogamy has increased for married couples since the 1970s, alongside the growth in overall income inequality.

The result is a stark class contrast, even in an age of soaring inequality: highly educated married or cohabiting employed women supplement their own high (relative to those of less educated women) earnings with their spouses’ or partners’ high incomes, and the poorest households are disproportionately headed by single mothers subsisting on extremely low wages.11

Class inequality is hardly a new phenomenon, but prior to the 1970s, when married women’s labor force participation rate far lower than it is today, the multiplicative effects of homogamy were relatively small. Considered in that light, class inequality among women in the United States has never been greater than in the twenty-first century. That seems unlikely to change in the absence of any significant policy interventions to address the problem of soaring inequality, whose victims include millions of women struggling to survive in the low-wage labor market.

Notes

- Sheryl Sandberg, Lean In: Women, Work and the Will to Lead (New York: Knopf, 2013).

- William Julius Wilson, The Declining Significance of Race: Blacks and Changing American Institutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980).

- Edward Gross, “Plus Ca Change. . . The Sexual Structure of Occupations over Time,” Social Problems 16, no. 2 (1968): 198-208; Ruth Milkman, Gender at Work: The Dynamics of Job Segregation by Sex during World War II (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987).

- The data for 1990 to 2000 are not strictly comparable to one another due to changes in the methodology used by the U.S. Census, but all available data suggest that the decline in segregation gradually leveled off, and was essentially flat after 2000. See Francine D. Blau, Peter Brummund, and Albert Yung-Hsu Liu, “Trends in Occupational Segregation by Gender 1970-2009: Adjusting for the Impact of Changes in the Occupational Coding System,” Demography 50, no. 2 (2013): 471-492.

- Institute for Women’s Policy Research, “The Gender Wage Gap: 2013,” Fact Sheet C413 (Washington, DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research, March 2014).

- The data shown in Figure 1 are decennial U.S. Census data (IPUMS) for workers aged 25-54. “Middle-class occupations” are defined as professional and managerial (including non-retail sales) occupations; all other occupations are considered “working class” in this analysis.

- David A. Cotter, Joan M. Hermsen, and Reeve Vanneman, “Gender Inequality at Work,” The American People: Census 2000 (New York: Russell Sate Foundation and Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau, 2004); see also Paula England, “The Gender Revolution: Uneven and Stalled,” Gender & Society 24, no. 2 (2010): 149-166; Ariane Hegewisch, Hannah Liepmann, Jeffrey Hayes, and Heidi Hartmann, “Separate and Not Equal? Gender Segregation in the Labor Market and the Gender Wage Gap,” Briefing Paper C377 (Washington, DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research, 2010).

- Ruth Milkman and Eileen Appelbaum, Unfinished Business: Paid Family Leave in California and the Future of U.S. Work-Family Policy (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013).

- Leslie McCall, “What Does Class Inequality among Women Look Like? A Comparison with Men and Families, 1970 to 2000,” in Social Class: How Does it Work? edited by Annette Lareau and Dalton Conley (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2008).

- On the contrast in working hours between women of different classes, see Jerry A. Jacobs and Kathleen Gerson, The Time Divide: Work, Family and Gender Inequality (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004). On intensive mothering and its relationship to social class reproduction, see Sharon Hays, The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996); Annette Lareau, Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003); and “An hereditary meritocracy,” The Economist, Jan. 24-30, 2015, pp. 17-20.

- Gary Burtless, “Effects of Growing Wage Disparities and Changing Family Composition on the U.S. Income Distribution,” European Economic Review 43 (1999): 853-865; June Carbone and Naomi Chan, Marriage Markets: How Inequality is Remaking the American Family (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014); McCall, “Class Inequality”; Sarah Damaske, For the Family? How Class and Gender Shape Women’s Work (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

© 2015 Ruth Milkman.