By Robert D. Francis

Were you the first in your family to graduate from college? If so, congratulations on defying the odds. During my dissertation fieldwork, I recently sat across the table from a young man who had tears in his eyes when he shared that he was the first in his family to finish high school. He hopes to go on to college, perhaps online, but he currently works as a laborer at a steel mill as he saves money and crafts his plan. Unfortunately, the data do not stand in favor of him finishing.

A new study from the National Center for Education Statistics or NCES (Redford and Hoyer 2017) gives a glimpse of the barriers that first generation (first-gen) college students face. When compared with what the study calls their continuing-generation peers, first-gen students were more likely to attend for-profit schools; half as likely to earn a bachelor’s degree by ten years from their sophomore years in high school; and more likely to leave college for financial reasons without a degree.

The NCES study might be particularly pessimistic because it uses a narrow definition of first gen: students enrolled in postsecondary education whose parents do not have any postsecondary education experience. What about those students whose parents have some college but no degree? What about an associate’s but not a bachelor’s? Or what if one parent earned a bachelor’s degree but left the family through divorce—or death? And what about those whose parents have a four-year degree but are still poor? Are any of these students first-gen too?

A recent article in The New York Times (Sharpe 2017) explored the challenges of defining first-gen. According to the article, the U.S. Department of Education defines first-gen in at least three different ways1. And a recent working paper (Toutkoushian, Stollberg, and Slaton 2015) finds that estimates of first-gen students in the Education Longitudinal Study of 2002—the same data source used in the NCES study—can range from 22 to 77 percent, depending on the definition. The first step in better serving first-gen students might be arriving at a shared definition.

A Shot at Middle Class

My case is one of the complex ones. I cannot claim first-gen status, as my Mom earned her bachelor’s degree in education at a rural teacher’s college. My Dad had his high school diploma, serving active duty as a Marine in Vietnam before settling into a career as a manual laborer.

We might have had a shot at the middle class on their joint incomes, but my Mom, despite her earning power, retired from teaching when I was born. Her view of gender roles, informed by her conservative Protestantism, dictated that she should stay home to raise me and my sister. This left my Dad to provide, and without the benefit of a college degree or union wages, it was always a struggle. While not first-gen, I grew up in what I now consider a working poor family, or perhaps working class, despite having one parent with a BA.

Common Approaches

Working class is another designation that is difficult to pin down. In an unpublished paper by sociologist and class scholar Allison Hurst, a review of sociological journal articles finds no consensus on how scholars operationalize social class. Common approaches utilize parental education or income, and to a lesser degree, parental occupation. None are fully satisfying, but more complex measures often require data not collected by most surveys. And still another vexing category is low-income.

What counts as poor? Should we use the federal poverty line, the supplemental poverty measure, Pell eligibility, or something else? Despite the lack of consensus in defining these terms—first-gen, working-class, and low income—we know there is quite a bit of overlap among these three designations. More practically, how do these first-gen and working-class identities play out on our campuses?

Overwhelmed and Familiar

There is good evidence that students from first-gen and working-class backgrounds not only face academic barriers, but cultural ones as well. First-gens can feel overwhelmed (Hertel 2002) and experience self-doubt (Engle, Bermeo, and O’Brien 2006). They often feel inauthentic (Dews and Law 1995; Lubrano 2004; Hurst 2010) on campuses where continuing-gen and middle-class values are the norm (Lightweis 2014; Pascarella et al. 2004; Reay et al. 2009; Stuber 2015).

I remember the jealousy and even resentment I felt toward my freshman roommate because he had his own desktop computer for our dorm room, while I relied on the campus computer labs to type and print my papers. I worked all through college, sometimes sending money home to help my family rather than the reverse.

And as if to crown my college experience with a final social class indignity, I remember my embarrassment when my family chose Bob Evans as the “nice” restaurant where we would celebrate my college graduation. It was what we could afford, and it was culturally familiar. (Truth be told, I didn’t have ideas for any nicer place anyway, which added to the insult as my classmates headed off to what I presumed were more upscale choices.)

Inequities in Education

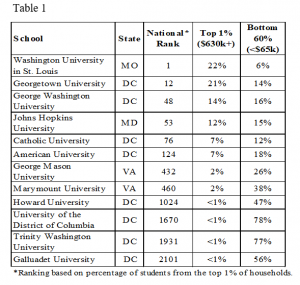

Some of the culture shock for first-gen and working-class students comes from the fact that our undergraduate populations are already polarized, unequal, and affluent. The Equality of Opportunity Project, led by Raj Chetty, made headlines in 2017 when one of their studies showed that 38 colleges and universities had more students from the top 1% of households than the bottom 60%. (The New York Times created an interactive tool with Chetty’s data that allows you to search for your school.2) Results for selected schools in the DCSS area are in Table 1.

Of course, these figures require interpretation, and they might say more about underlying inequalities in education writ large than about any particular institution. Regardless of the composition of our undergraduate populations, there is much that can be done to consider the unique needs of our first-gen, working-class, and low-income students.

Measure and Proxy

The first step for many schools is collecting better data. The Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), the financial aid form completed by most incoming freshman, has just one crude measure of parental education.

Marymount University in Arlington, where I am an adjunct faculty member, started asking additional questions about first-gen status in their application in 2010. For most schools, Pell eligibility provides a proxy for low-income. Even for schools that track low-income and first-gen, measures of social class are still largely absent. We can start by collecting better data about the first-gen, working-class, and low-income statuses of our students.

Some schools provide infrastructure to support the unique needs of these students. Marymount University’s Office of the First-Year Experience3, while not explicitly dedicated to first-gen and working-class students, focuses on the social and academic transition to college, which can be more fraught for first-gen, working-class, and low-income students. Campuses are also forming student groups for low-income, first-gen, and working-class students, like First-Gens@Michigan. And sociology faculty, for their part, are finding ways to add social class considerations into their curriculum4.

But as Debbie Warnock (2016) recounts, her efforts as a faculty member to sponsor a first-gen, working-class, and low-income student group ran into many institutional hurdles. From this experience, she drew the provocative conclusion that low-income students lack institutional support because their very existence challenges the bottom lines of their schools: they cost more to admit and sustain, and their lower test scores and poorer graduation rates punish schools in the arms race of the hallowed college ranking systems.

I was recently at a coffee shop in my rural hometown when I noticed that the barista on duty was studying when business was slow. I asked her about her story. She said she started at a selective liberal arts college about an hour away, but the privilege of her fellow students was unexpected and jarring. She loved her classes and professors, but she said she felt isolated and alone. She left the school after just one semester. Now she is working toward her Associate of Arts (AA) degree at a small branch campus closer to home. Her classes are much less challenging, but the school is a cultural fit. She may be fine in the long run, but how many other stories like hers go unnoticed each semester? Many of the efforts to support first-gen and working-class students on campus are led by faculty and staff who themselves identify as first-gen or working-class.

And just as first-gen and working-class undergraduates face challenges, so do scholars with those backgrounds. There is evidence that first-gen and working-class academics often feel like they don’t belong (Lee 2017). And while definitive data are lacking, there is still reason to believe that first-gen and working-class scholars are more likely to end up as contingent and non-tenure track faculty (Soria 2016).For those who can relate, a new edited volume of essays, Working in Class: Recognizing How Social Class Shapes Our Academic Work (2016), offers empathetic voices. The thirteen essays explore what it means to be a working-class academic in the three primary domains of academic life: teaching, research, and service. These essays are also worthwhile for scholars from more advantaged backgrounds, as they reveal ways in which we all might unintentionally reinforce class-based inequalities in the classroom and our faculty interactions.

There is also the Working-Class Studies Association5, formed in 2003 “to promote the study of working-class people and their culture.” This professional association includes a Working-Class Academic Section, designed specifically as a place for scholars who identify as working class.

ASA Task Force

The American Sociological Association (ASA), for its part, is wading into these discussions with the formation of a new Task Force on First-Generation and Working-Class People in Sociology6. Called into existence by the ASA Council thanks in part to agitation by working-class sociologists, the Task Force—chaired by Vincent Roscigno from Ohio State University—has a three-year charge to explore the state of first-gen, working-class, and low-income people within the discipline. I was fortunate to be named as one of the Task Force’s thirteen members. We began our work in late 2017, which will continue through 2020. Look for us at the 2018 ASA Annual Meeting in Philadelphia. If you have thoughts about the place of first-gen and working-class people within sociology, please reach out to me at [email protected]. This Task Force presents a unique opportunity to make sure the discipline of sociology is no longer skipping class.

Notes

- The definitions are: no parent in the household has a bachelor’s degree; no education after high school; no degree after high school.

3. https://www.marymount.edu/Admissions/Accepted-Students/First-Year-Experience

4. http://www.everydaysociologyblog.com/2018/02/the-big-rig-and-the-sociology-of-work.html#more

References

Dews, C. L. Barney, and Carolyn Leste Law, eds. 1995. This Fine Place So Far From Home: Voices of Academics from the Working Class. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Engle, Jennifer, Adolfo Bermeo, and Colleen O’Brien. 2006. “Straight from the Source: What Works for First-Generation College Students.” Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education. ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED501693.

Hertel, James B. 2002. “College Student Generational Status: Similarities, Differences, and Factors in College Adjustment.” The Psychological Record. 52(1): 3-18.

Hurst, Allison L. 2010. The Burden of Academic Success: Loyalists, Renegades, and Double Agents. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Lee, Elizabeth M. 2017. “‘Where People Like Me Don’t Belong’: Faculty Members from Low-socioeconomic-status Backgrounds.” Sociology of Education. 90(3): 197-212.

Lightweis, Susan. 2014. “The Challenges, Persistence, and Success of White, Working-class, First-generation College Students.” College Student Journal 48(3): 461-467.

Lubrano, Alfred. 2004. Limbo: Blue-Collar Roots, White-Collar Dreams. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Pascarella, Ernest T., Christopher T. Pierson, Gregory C. Wolniak, and Patrick T. Terenzini. 2004. “First Generation College Students: Additional Evidence on College Experiences and Outcomes.” The Journal of Higher Education. 75(3): 249-284.

Reay, Diane, Gill Crozier, and John Clayton. 2009. “‘Strangers in Paradise’? Working-class Students in Elite Universities.” Sociology 43(6): 1103-1121.

Redford, Jeremy and Kathleen Mulvaney Hoyer. 2017. “First-Generation and Continuing-Generation College Students: A Comparison of High School and Postsecondary Experiences.” National Center for Education Statistics. Available at https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018009.pdf.

Sharpe, Rochelle. 2017. “Are You First Gen? Depends Who’s Asking.” The New York Times. Nov 3.

Soria, Krista M. 2016. “Working Class, Teaching Class, and Working Class in the Academy.” In Hurst, Allison L., and Sandi Kawecka Nenga. Working in Class: Recognizing How Social Class Shapes Our Academic Work. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Stuber, Jenny M. 2011. Inside the College Gates: How Class and Culture Matter in Higher Education. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Toutkoushian, Robert K., Robert S. Stollberg, and Kelly A. Slaton. 2015. “Talking ‘bout My Generation: Defining ‘First-generation Students’ in Higher Education Research.” Association for the Study of Higher Education-40th Annual Conference.

Warnock, Deborah M. 2016. “Capitalizing Class: An Examination of Socioeconomic Diversity on the Contemporary Campus.” In Hurst, Allison L., and Sandi Kawecka Nenga. Working in Class: Recognizing How Social Class Shapes Our Academic Work. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Fine article. — Jim Loewen