By Lester R. Kurtz

“They hired me to kill people, so I can’t remember people’s names,” an inebriated gentleman across the aisle explained to us after his companion complained that he had called him by the wrong name one recent morning at Starbucks. He had seen years of combat, he’s “the one they called in when someone needed help.” He was now clearly the one in need of help rather than the rescuing hero. As I write, the Commander-in-Chief of the world’s largest military has teared up while talking about the deaths of first graders in a school shooting, and North Korea has claimed to have tested a hydrogen bomb.

Fighting violence has been a top priority on my intellectual agenda for decades. Max Weber said we have to wrestle with the demon of our time — for him it was bureaucratization, rationalization; for me, it is violence. Years ago, wanting to delve deeper into the causes of violence and its remedies, I combined my interest in the sociology of religion with a newer one in the arms race and the problem of violence.

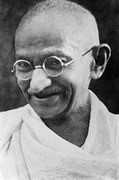

I turned to one of my favorite authors from my anti-Vietnam War college days: Mahatma Gandhi. Off I went to India for a year of interviews and field work, reading and searching.

The Warrior and The Pacifist

From studying Gandhi’s legacies, I have learned this: the world’s religious and ethical systems present us with contradictory motifs regarding the use of violence and force: the warrior and the pacifist (Kurtz 2008).

The warrior believes in a sacred duty to use violence on behalf of a higher cause. The pacifist, however, believes it is a sacred duty not to harm or kill others. These contradictory motifs, internalized by many, precipitate a structural ambivalence in various social roles (Merton and Barber 1976). Gandhi’s nonviolent activist embraces both motifs and transcends them, fighting without killing.

Both warrior and pacifist roles are fraught with dilemmas. The warrior knows there are moral problems with killing, and much combat research suggests killing under any circumstance causes psychological harm to the perpetrator (Grossman and Siddle 2008; MacNair 2002; Collins 2009) and high levels of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among combat veterans (like our Starbucks friend) provide an indicator.

When I interviewed the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, he insisted that humans were born nonviolent — our first act is to seek nurture at our mother’s breast — and we have to be taught to be violent. The pacifist, however, may be rendered ineffective in the face of injustice, paralyzed by concerns about harming others if she or he acts to address a problem. Sitting on the sidelines of history, the pacifist’s moral stance paradoxically fails to take the offensive and challenge evil, thus creating another moral dilemma.

The Nonviolent Activist

Because the warrior has to account morally for his or her questionable behavior to himself or herself and others (Bandura 1999), religion becomes a powerful and widely available resource for justifying the use of violence. Violence becomes sacralized and is transformed from a sin to a duty; under such circumstances, what is usually forbidden, becomes obligatory (Girard 1977).

Gandhi addresses the shortcomings of both motifs with the nonviolent activist; his fusion of contradictory moral teachings results in a burst of cultural creativity that draws on ancient faith traditions but offers alternatives for the future. It diffuses globally in human rights and pro-democracy movements; it has led to the fall of the apartheid system in South Africa, the collapse of dictatorships, and significant cultural and policy shifts worldwide over the ensuing decades.

Ambivalence about Violence

Fighting violence becomes acutely problematic in the nuclear age, in which, Jonathan Schell (2002:195) argues “morality and action inhabit two separate, closed realms. All strategic sense becomes moral nonsense, and vice versa, and we are left with the choice of seeming to be either strategic or moral idiots.” Nonviolent civil resistance, Gandhi argued, allows one to be both morally and strategically smart. This ambivalence about violence and Gandhi’s struggle against it emerged quickly in my research on his legacies.

When Gandhian-trained Jawaharlal Nehru transitioned from nonviolent civil resistance to governance, he found himself caught in a classic Weberian dilemma: “he who lets himself in for politics, that is, for power and force as means, contracts with diabolical powers” (Weber 1948:123). As soon as he took office, the atrocities of communal violence “required” the resistor turned prime minister to send troops to quell the violence. The first interview I conducted in India was with a seasoned Gandhian activist, who declared Nehru was the devil who had betrayed the Mahatma. Yet, when the Chinese invaded the Indian border in 1962, critics claimed Nehru had failed to build up India’s military. He could please neither warriors nor pacifists.

John Kenneth Galbraith, President Kennedy’s ambassador to India who became close to Nehru, told me that the Chinese invasion destroyed Nehru; he died a few months later. Personal and political dilemmas about violence are intertwined.

Types of Violence

Gandhi’s multi-faceted fight against violence took place on two “fronts:” on the one hand was nonviolent resistance of the system he opposed (British colonialism) and on the other, his “constructive program” that involved building up alternative institutions that would serve the new society after the old one had fallen (an aspect too often neglected by today’s social critics).

The Violence Diamond (Kurtz 2015), adapted from Galtung’s (1990) Violence Triangle. Source: Lester R. Kurtz.

In doing so, he addressed all of the major types of violence later conceptualized by Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung (1990): structural violence (harm caused by social structures), cultural violence (racism, imperialism, discrimination), and direct violence (what we usually think of as violence). In my conceptual resistance of violence, I have added a fourth side to Galtung’s triangle, “ecoviolence,” which is violence against the natural environment, which has become more prominent since the publication of Galtung’s 25-year-old typology.

Gandhi’s social theory was created out of and resulted in his praxis: mobilizing creative collective action against multiple forms of violence. His campaigns against the British Raj (systemic cultural racism and global structural inequality reinforced by the brute force of the British military) were accompanied by campaigns against “untouchability” (the extreme of the caste system) and patriarchy (although I do not think he called it that).

Here is how it worked, taking the two prime examples from his resistance to Empire: the cloth boycott and the Salt March. The former went to the heart of the colonial system of resource extraction (which persists today in relations between “the West” and the “South”). He called on Indians to spin their own clothes and boycott British products, allowing mass direct protests by individuals who could protest the Raj with low-risk daily actions that empowered them to address their own basic needs. The Indian National Congress gave out spinning wheels; recipients could participate in the revolution by spinning their own clothes.

The second iconic campaign was the Salt March, in which he again brought macro issues to the micro level, marching 240 miles to the Indian Ocean to defy the British monopoly on that basic ingredient for everyday life, and promoting indigenous production of salt from their own natural resources. Arriving on the anniversary of the Amritsar massacre where nonviolent demonstrators had been gunned down by British troops, Gandhi kicked off the final major campaign that facilitated the move to Indian Independence and the eventual unraveling of the colonial system.

If the lessons from Gandhi’s struggle against violence are to be better understood and actualized, we need more public sociology. That is at the top of my agenda, and I invite you to join me.

References

- Bandura, Albert. “Moral Disengagement in the Perpetration of Inhumanities.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 3 (1999): 193–209.

- Collins, Randall. Violence: A Micro-Sociological Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

- Galtung, Johan. “Cultural Violence.” Journal of Peace Research 27 (1990): 291–305.

- Girard, Rene. Violence and the Sacred. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1977.

- Grossman, Dave, and Bruce Siddle. “Psychological Effects of Combat.” In Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace and Conflict. L. R. Kurtz, editor, 1796–1805. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2008.

- Kurtz, Lester R. “Gandhi and His Legacies,” 2008. In Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace and Conflict. L. R. Kurtz, editor, 1796–1805. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2008.

- MacNair, Rachel. Perpetration-Induced Traumatic Stress: The Psychological Consequences of Killing. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2002.

- Merton, Robert K., and Elinor Barber. “Sociological Ambivalence.” In Sociological Ambivalence and Other Essays, 3–31. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1976.

- Schell, Jonathan. The Fate of the Earth: And, The Abolition. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000.

- Weber, Max. “Politics as a Vocation.” In From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, Hans Gerth and C. Wright Mills, editors. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 1948.

A very thoughtful narrative in my opinion Ideas of Gandhi prepare the ground for instituting Sociology of Peace and Non- Violence. The social actions of Gandhi are neither Zweckrational nor wertrational they comprise emotional-moral construction in which truth and sacrifice are components Gandhis ideas are messages as well an strategic practices.