Tucked away from D.C.’s busy beltway lies Mount Vernon, the former estate of the first President of the United States. The 500-acre property was inherited by George from his father in 1761 and was purchased by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association in 1858 to save the estate from ruin. Today, Mount Vernon is operated by the Association as an historic site that includes museums, Washington’s presidential library, and vintage farmsteads. But, the museum at Mount Vernon lightly touches upon the legacy of slavery in Washington’s personal and professional life, and the topic is obscured in ways that sit uneasily.

Museums and historical sites like Mount Vernon are purveyors of information that frame how we view our social world. The ways in which slavery is presented at Mount Vernon matter ideologically in terms of what Eduardo Bonilla-Silva describes as “expressions at the symbolic level of the fact of dominance” (2014:74). If we consider this definition of ideology, then we can consider how slavery is expressed symbolically at Mount Vernon. In a dominant symbolic expression, history is framed in “set paths for interpreting information” (Bonilla-Silva 2014:74). It is therefore important that we “undertake an exacting political and ethical critique of…ideologies of difference” (Mbembe 2017:177) as we follow tours and signposts.

At Mount Vernon, it would be easy to imagine a visitor who only thinks of slavery briefly, who “hears so little that there almost seems to be a conspiracy of silence; the morning papers seldom mention it, and then usually in a far-fetched academic way, and indeed almost everyone seems to forget and ignore the darker half of the land, until the astonished visitor is inclined to ask if after all there is any problem here” (DuBois1994:110). Upon entering the estate, visitors are ushered into a room where an introductory film called We Fight to be Free is screened. The film is an unapologetic tribute to Washington, who is portrayed as a morally impeccable revolutionary hero (Van Oostrum 2006).

The role of slave labor in contributing to Washington’s vast wealth—one of the richest presidents in United States history—goes mostly unmentioned. Our tour guide described the present-day estate as a “working plantation” with no sense of irony as to what a working plantation would entail if it were to include period-relevant slaves.

Progressing further along the tour, the absence of slavery becomes louder as we read maps that breezily describe the location of slaves’ quarters alongside prized fruit gardens. We climbed staircases to peer at Martha Washington’s closets and hear about her shopping habits.

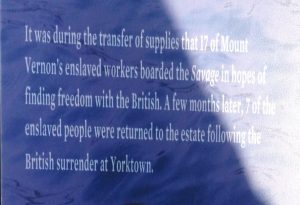

The pockets of information where slavery is discussed are fragmented: ensconced in a museum deep in the main building, on a placard outside the boating dock, and in an isolated reconstruction of a slave’s cabin. The museum exhibit Lives Bound Together: Slavery at George Washington’s Mount Vernon (MacLeod 2016) provided personal details of slaves who were kept at Mount Vernon, but kept them at a distance from Washington’s narrative. Mount Vernon’s official website does contain a special section on slavery with over two dozen entries on subjects like Slavery at Mount Vernon, and Martha Washington as a Slaveowner (Mount Vernon 2019b). The archival nature of a website cannot be expected to be reproduced in an hour-long tour.

Perhaps most interestingly, the term “enslaved peoples” (used throughout the literature, displays, and guided tours at Mount Vernon) was deliberately chosen over the word “slaves.” A display panel in the Lives Bound Together exhibit addressed the word choice. The language, it states, was used intentionally so as to invoke the “humanity” of the slaves (MacLeod 2016). However, as Mbembe has problematized, the “idea of a common human condition is the object of many pious declarations. But it is far from being put into practice” (2017:161). Instead, a political economy approach that considered the role of slave labor in Washington’s wealth, for example, might provide an ontology that acknowledges both the labor of slave bodies and their exploitation. For, “the term ‘Black’ was the product of a social and technological machine tightly linked to the emergence and globalization of capitalism” (Mbembe 2017:6). This might even provide more support for the argument for reparations.

The guided tour ended in Mount Vernon’s kitchen where slaves labored in the pre-dawn to keep the residents fed. During my visit, one tourist marveled at the cook’s ability to rise so early. The tour guide missed an opportunity to inform guests why a slave (such as Washington’s personal favorite chef, Hercules, who later attempted escape) would be obliged to rise early. Instead, the tour ended, and the questioning tourist who exited through the kitchen’s back door had the same fate as DuBois’ “casual observer visiting the South” who “notes the growing frequency of dark faces as he rides along, – but otherwise the days slip lazily on, the sun shines, and this little world seems as happy and contented as other worlds he has visited.” (1994: 110).

References

Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2014. Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America. 4th ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Du Bois, W.E.B. 1994. The Souls of Black Folk. New York: Dover Publications.

MacLeod, Jessie, curator. October 1, 2016-September 30, 2020. Lives Bound Together: Slavery at George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Mount Vernon, VA: Donald W. Reynolds Museum and Education Center.

Mbembe, Achille. 2017. Critique of Black Reason. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Mount Vernon. 2019a. “Hercules.” Retrieved May 1, 2019 (https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/hercules/)

Mount Vernon. 2019b. “Slavery.” Retrieved May 1, 2019 (https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/slavery/)

Van Oostrum, Kees. 2006. We Fight to be Free. DVD. Los Angeles, CA: Greystone Films Inc.