By C. Soledad Espinoza

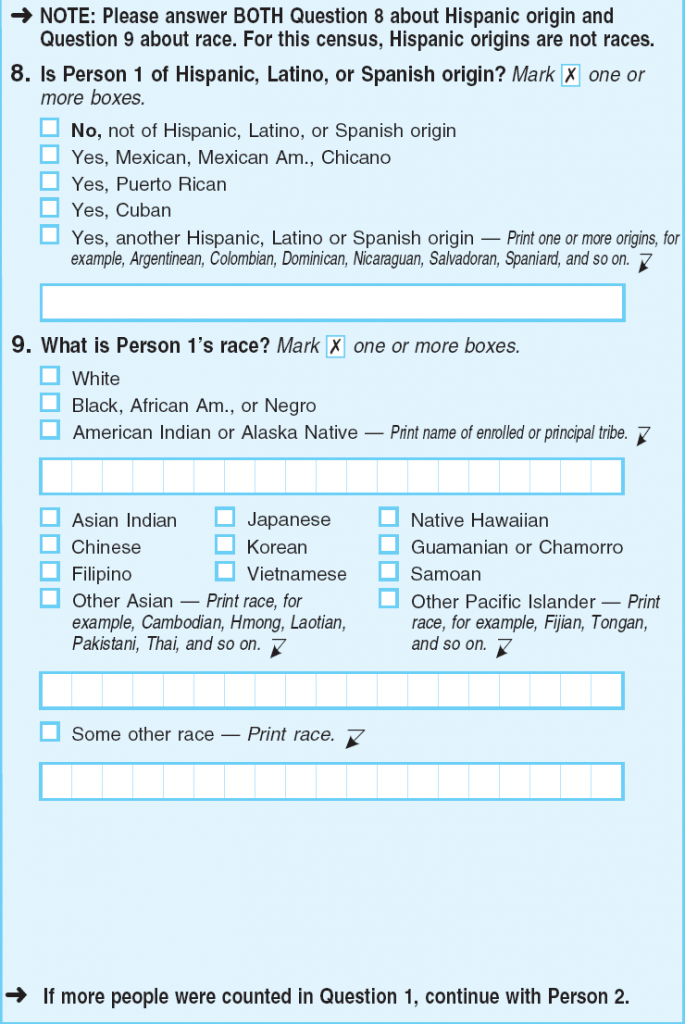

Based on the 1997 federal standards (Office of Management and Budget or OMB Statistical Policy Directive No. 15), the U.S. Census Bureau asks all American residents to identify a race category apart from identifying ethnicity on the decennial census. In the most recent 2010 survey, the question for ethnicity asks if the respondent is Hispanic/Latino1 or not Hispanic/Latino noting that, “for this census, Hispanic origins are not races.” Yet the included race categories relate to ethnic content (e.g. language), legal content (e.g. tribal enrollment), and geographic origin (e.g. continent-level or state-level). Various non-Hispanic origins are included in the race question as check boxes or written examples (e.g. Chinese, Chamorro, and Hmong). The census question for Hispanic origin is the only origin group treated separately and apart from other origin groups.

Though the census form is structured to require all respondents to report race in addition to a response for Hispanic ethnicity, many Hispanics do not comply in reporting a standard OMB race category.2 Instead, over a third of Latinos use the residual race category, “Some Other Race” U.S. Census Bureau 2011). In a large number of these cases (over 80 percent), Hispanic respondents write in what is typically considered to be a U.S. ethnic origin term like “Latino” or “Mexican” U.S. Census Bureau 2014a). These self-reported responses to the race question suggest that for many Hispanics, the origin terms are appropriate responses within the schema of the standard OMB race categories. That is, the terms are meaningful options that relate yet are distinct from the standard OMB race options.

In the 2010 Alternative Questionnaire Experiment (AQE), the U.S. Census Bureau tested a combined race and ethnic origin question as part of its planning for the 2020 census U.S. Census Bureau 2011). The AQE study shows that a different pattern of race reporting emerges among Hispanics when the race and Hispanic ethnicity questions are combined.3

Less than one-in-five Latinos report as white. In contrast, about half of Latinos report as white when race and ethnicity are asked as separate questions (U.S. Census Bureau 2011).4

As historical context, early legal precedence conferred institutional whiteness to people with Latin America origins despite persistent social exclusion from whiteness in the U.S. (Gómez 2007). Edward Telles,5 a Princeton University sociologist and author of Generations of Exclusion: Mexican-Americans, Assimilation, and Race (2008), provides an example, “Mexicans were long racialized in the U.S. southwest, i.e. popularly seen and treated as a race separate from whites, Chinese, African Americans, etc. But they were made citizens and thus de facto given white status under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848.” At that time, whiteness was a requisite for U.S. citizenship and the protection of one’s legal rights.

“Mexican” was first included in the U.S. census as a race option in 1930. During a period of great racial fear, lack of civil rights protections, and political backlash, Mexican as a race option was removed in the subsequent decennial census. Since then, the Hispanic origin question has never been re-integrated with the standard (OMB) race options into a combined census question. Yet various studies find the Hispanic reporting of whiteness with the census-like (two-question) format to be highly inconsistent, difficult to substantively interpret, and, most concerning, inaccurate (Telles 2008; JBS International, Inc. 2011; Dowling 2014). These studies show that when researchers use a combined question format or follow-up interviews they find that many Latinos who report as white under a two question (census-like) format explain that they do not actually identity as white.

In the contemporary U.S. context, many Latinos and Latino scholars reject whiteness as the social reality of Hispanics (Gómez 2007; Telles 2008; Dowling 2014).

The formal categorization of whiteness attributed to Latinos is a contradiction of the “one-drop rule” experienced by Americans of black descent and the racialized experiences of Latinos and multi-racial persons within the U.S. Including Hispanic origins in a census race and origin question may better allow Latinos to self-report as they see themselves. According to Julie Dowling,6 a University of Illinois sociologist and author of Mexican Americans and the Question of Race (2014), “asking for ‘race or origin’ accommodates the different ways Latinos may see their identities.”

There are also other implications, Dowling continues, “my concern has actually been that people interpret the census racial responses for Latinos as a measure of skin color, when for many (or even most) it is not. Moreover,…the news media has at times reported that Latinos are assimilating and no longer facing discrimination based on the number who label as ‘white.’ And this really concerns me, especially because my research reveals that Mexican Americans in Texas are highly racialized despite the fact that many identify as white on the census.”

An additional issue is the equitable treatment of Latinos, which was reported as a concern in the AQE study when focus group participants discussed the two-question race and ethnicity format (JBS International, Inc. 2011). Dowling characterizes this as a disadvantage in the current census format, “many Latinos felt stigmatized by the separate question, while non-Latinos thought it was preferential treatment.”

Past researchers have characterized the distinction between U.S. race and ethnic categories to be arbitrary. In 1997, the American Anthropological Association (AAA) 7 recommended that Directive No. 15 combine the race and ethnicity categories into one question. AAA noted that “race and ethnicity categories used by the Census over time have been based on a mixture of principles and criteria, including national origin, language, minority status and physical characteristics.” Three census forms later, it is not clear if all American origins will be combined into one race and ethnicity question or separated across two questions. Planning for the 2020 census at the U.S. Census Bureau is still underway, and a final decision has not been made yet (U.S. Census Bureau 2014b).

Amidst concerns about data accuracy and validity, research suggests that the present census (two-question) format may compromise the scientific, legal, and social value of the important (and costly) information collected on race and ethnicity. The U.S. Census Bureau has a mandate to collect the national data that underlie civil rights enforcement, budgetary allocations, and electoral representation. It is a critical national and local concern that the agency may not be appropriately measuring identity for Latinos—the second largest ethno-racial group in the country (U.S. Census Bureau 2011).

Notes

- The terms Latino and Hispanic are used interchangeably in this article.

- The standard OMB race categories are White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.

- The AQE tested format includes the option of choosing multiple race and ethnic origin responses.

- The percent of Latinos that self-identify as black reported in the combined question format is found to be comparable to the percent of self-identified Afro-Latinos using a separate question format (JBS International, Inc. 2011). Other research shows that responses to the census-like format generally do not match color for Latinos despite some interpretations in the media that race reporting by Latinos reveal color variation within the group (Telles 2008, Rodriquez 2000, Dowling 2014). Per Telles, “if persons that are perceived as Afro-Latino don’t see themselves that way, then we are unlikely to pick that up in a Census question on self-identification.”

- Dr. Edward Telles is author of Pigmentocracies: Ethnicity, Race, and Color in Latin America (2014) and Generations of Exclusion: Mexican-Americans, Assimilation, and Race (2008).

- Dr. Julie Dowling is author of Mexican Americans and the Question of Race.

- According to correspondence with the American Sociological Association (ASA) for this article, the ASA does not have available official statements directly related to the 1997 OMB federal standards (or the recent AQE format testing at the U.S. Census Bureau) on race and ethnicity.

Works Cited

- Dowling, Julie. 2014. Mexican Americans and the Question of Race. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Gómez, Laura E. 2007. Manifest Destinies: The Making of the Mexican American Race. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- JBS International, Inc. 2011. “Final Report of the Alternative Questionnaire Experiment Focus Group Research.” Bethesda, MD. JBS International.

- Telles, Edward. 2014. Pigmentocracies: Ethnicity, Race, and Color in Latin America. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Telles, Edward and René Flores. 2013. “More than Just Color: Whiteness, Nation and Status in Latin America.” Hispanic American Historical Review 93(3): 411-449.

- Telles, Edward and Vilma Ortiz. 2008. Generations of Exclusion: Mexican-Americans, Assimilation, and Race. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. “Census Race and Hispanic Origin Alternative Questionnaire Experiment.” Suitland, MD: U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2011. “Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010.” Suitland, MD: U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2014a. “Race Reporting Among Hispanics: 2010.”Suitland, MD: U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2014b. “The 2010 Census Race and Hispanic Origin Alternative Questionnaire Experiment.” Presented at Pew Research Center March 12, 2014.