The motto of Howard University, “In Truth and Service,” is embodied by its scholars, students, and faculty. A century ago, Dr. Kelly Miller established the Department of Sociology to uncover the truth about the “race problem” in the United States. Since 1919, the mission of the department has been “to prepare students to analyze, transform, and overcome conditions of oppression, exploitation and injustice” (Howard University 2020). Howard University, notably called the Mecca, was “for scholars leading the intellectual discourse on the most pressing problems of Blacks in the U.S. and Africa, problems associated with race ideology, economic power, and social class” (Jarmon 2003). The Department became a home for scholars who believed in centering issues of inequality which marginalized the Black community.

Howard University is the only Historically Black College and University (HBCU) in the United States with a doctoral program in sociology. Within the nation’s capital, the Department is also the only program in the District of Columbia that offers a Ph.D. in sociology. The Department has produced a wave of Black Ph.Ds. in sociology and cultivated generations of Black leaders in communities, organizations, and institutions. Legendary scholars in the Department, such as Kelly Miller, E. Franklin Frazier, Joyce Ladner, and Andrew Billingsley, have contributed to the discipline of sociology and enhanced the scholarship on Black American life. The Department continues to be a powerhouse of Black intellectual thought and upholds the legacy of truth and service.

The Beginnings

At the turn of the 20th century, Howard University was the only institution for Blacks with University status. Like most HBCUs, its purpose was to educate Blacks in trade, particularly in agricultural, mechanical, and industrial subjects, for the workforce (Office for Civil Rights 1991). In the 1890s, Howard University began to adopt a liberal arts framework over vocational training, which led to a period of curricula and scholarship expansion (Jarmon 2013). Howard became a Mecca for Black scholars and students who were interested in social sciences and disciplines outside of industrial education (Jarmon 2013). Black scholars, including Dr. Kelly Miller, lectured about the “race problem” within the United States during the 1890s (Jarmon 2003).

Dr. Kelly Miller Source: Casey Nichols. 2007. Kelly Miller (1863-1939).

Miller believed that sociology provided an “objective perspective on questions of race and social inequality” (Jarmon 2003:366). In 1903, Miller piloted a new sociology course at Howard, and by 1919 the Department of Sociology was founded. Miller would serve as chairman until 1925, expanding the scope of the program’s courses and faculty. Howard has long been dedicated to the study of racial relations in society. During Miller’s tenure as chair of the Department, the curriculum included traditional sociological theory and methods but centered social inequality and race (Jarmon 2003).

The Frazier Era

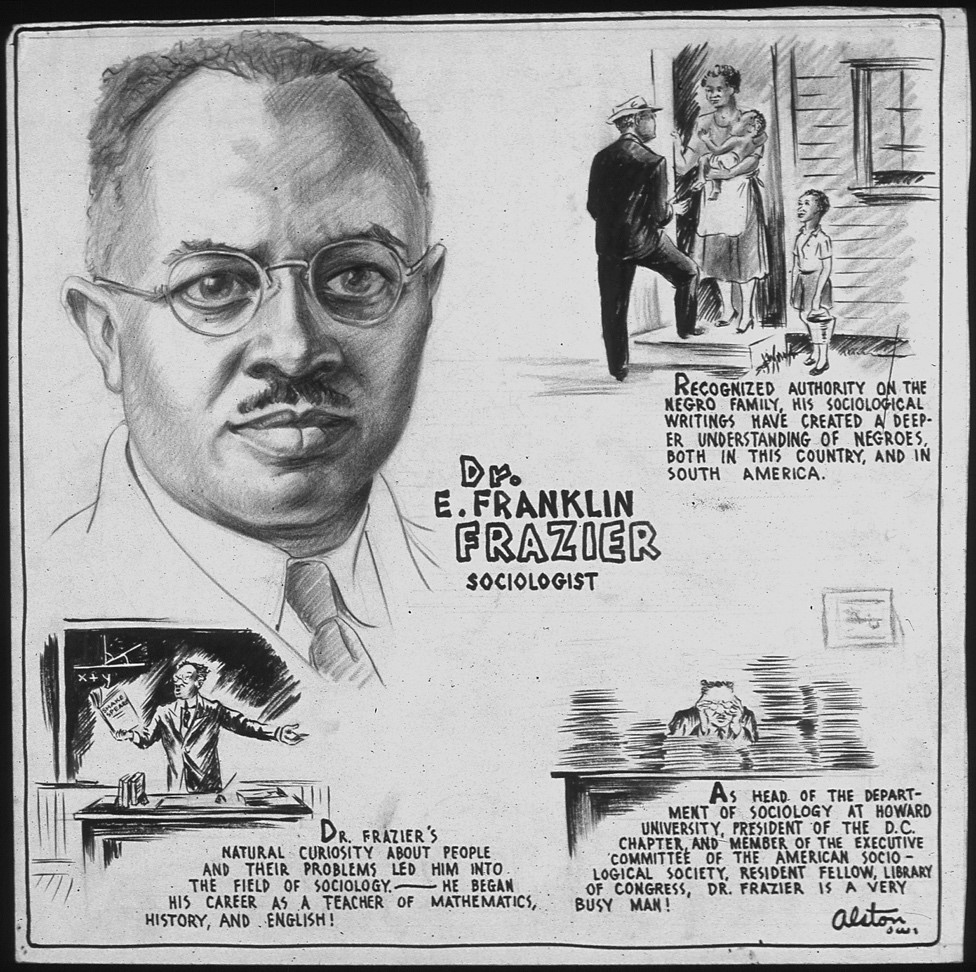

Blacks continued to demand more educational opportunities and college-level courses outside of vocational training throughout the U.S. in the early 20th century. Howard University and other HBCUs were fighting against structural and political forces that tried to limit higher education for Blacks. E. Franklin Frazier, who assumed the position of chairman in the Department in 1934, strived for academic rigor that could rival departments at primarily white institutions (Jarmon 2003). In his first year, he revamped the curriculum, increased the educational standards of the Department, and instituted the M.A. program (Jarmon 2003; Platt 1991). Frazier and his protégé, G. Franklin Edwards, continued to consolidate the department and add courses that addressed the challenges of the Black community (Jarmon 2003). Frazier’s advocacy for using theory in practice and for the continuous pursuit of research and social policy for Black Americans would inspire the Department for decades to come.

The notion of biological determinism and the innate inferiority of the Blacks permeated social science research throughout the early 20th century (Dingwall, Nerlich, and Hillyard 2003; Jarmon 2013; Miller and Costello 2001; Platt 1991). In continuing Kelly’s mission to bring objectivity and truth to the race question, Frazier was committed to producing studies against scientific racism (Jarmon 2013). Frazier, much like his mentor W.E.B. Du Bois, wrote controversial pieces on race, class, and the reality of Black American life. In 1939, he published The Negro Family in the United States, which challenged the view of biological inferiority of Blacks and centered social and economic relations (Jarmon 2013).

Left to Right: James Nabrit, Charles Drew, Sterling Brown, E. Franklin Frazier, Rayford Logan, Alain Locke. Source: Moorland Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

Frazier became known for his scholarship on race relations within the United States and globally. In 1948, Frazier was elected by the American Sociological Association (ASA) as the first Black president. In his ASA Presidential Address, Frazier stated that “sociology as an academic discipline did not deal specifically with the problem of race relations” and his role was to bring attention to this phenomenon within the discipline (Frazier 1949:2). Following this address, Frazier published two of his most renowned books, The Negro in the United States (1949) and The Black Bourgeoisie (1955). Frazier’s recognition of the need for new perspectives and to adjust to an ever-changing society planted seeds of change within the Department and the discipline (Jarmon 2003).

The Transformative Years

The Civil Rights Era brought social and political change, not only in the Department but in the wider society. Howard’s Sociology and Anthropology Departments merged in 1957, and Mark Hanna Watkin, the first African American to earn a Ph.D. in anthropology, became the Department chair from 1961 to 1968 (Davis 2019; DPAAC Staff 2016). Students were influenced by the movements and ideologies of the time and demonstrated against the curriculum of the Department. Students resisted the mainstream sociological perspectives being taught because they deemed it to be “too conservative and promoted the incipient movement towards Black sociology and dialectical materialism” (Jarmon 2003:370). Their resistance and the subsequent curriculum adjustments continue to influence the teaching of sociology in the Department today.

From the late 1960s to 1970s, the Department shifted towards a more radical sociological perspective which “combined elements of the Internal Colonial model, the Historical Materialism model, the Pan-African model, and the Critical Race model” (Gomes 2018:10).

Howard University Student Protest Organizing meeting, 1968. Source: Kyra Azore, The Hilltop News Reporter. 50 Years Later: The Demonstration that Changed Howard and the Legacy it Left.

During this transformation, the Department added new faculty to revamp the program. With the addition of Dr. Joyce Ladner, Dr. Robert Staples, Dr. Ralph C. Gomes, Dr. Jonnie Daniel, and Dr. Joan Harris to the faculty, the curriculum unapologetically focused on topics of scholar activism, the Black community, and a critical analysis of the discipline. Ladner, who later became chair of the Department, was a catalyst for change by expanding the curriculum to encourage perspectives outside of Euro-American sociological theories (Gomes 2018). With the influx of new faculty and the expanding need to develop Black sociology, the Ph.D. program was established by Dr. Gomes in 1974 (Gomes 2018). Urban sociology, intergroup relations, social control and deviance, social organizations, and social psychology were concentrations offered within the doctoral program (Gomes 2018). These specializations centered around social issues within the Black community and influenced the scholarship of future scholars matriculating through the program. Dr. Ivor Livingston, who received the first sociology doctorate degree from the Department in 1979, later became, and continues to be, a professor within the Department.

Howard University Student Sit-in of the Administration Building, 1968. Source: Kyra Azore, The Hilltop News Reporter. 50 Years Later: The Demonstration that Changed Howard and the Legacy it Left.

Considering economic and political movements during the 1980s and 1990s, many policies were impacting communities across the United States. Specifically, new racial politics and social policies, such as the War on Drugs and the disappearing social safety net, transformed the lives of people of color and women (Alexander 2012; Williams 2003). The Department was affected by the increasing financial restrictions happening in the broader society and at most HBCUs. Since the 1990s, the Department has reduced the number of faculty, decreased financial support for graduate students, and reduced the number of specializations (Gomes 2018). The Department became more interdisciplinary by collaborating with other Howard graduate programs and professional schools which gave it flexibility to adapt to the changing environment (Gomes 2018). Although the Department has felt the effects of the financial crisis of the 2000s and reduced funding allocations, it continued to matriculate cohorts of M.A. and Ph.D. students through the program and produce dozens of studies and articles.

Public Sociology in the New Millennium

Since 1895, the instruction of sociology at Howard University has focused on increasing the collective understanding of social inequality and race. Between 1997 and 2002, thirty-four articles on social inequality and or race relations were published by scholars within the Department. During the early 2000s, much of the Department’s coursework examined several dimensions of inequality, statistics, methods, social psychology, and administrative justice (Jarmon 2003).

The Department also embraced criminology as a critical area of study within sociology, and in 2016 changed its name to the Department of Sociology and Criminology. Although public sociology gained popularity in mainstream sociology, the Department has always been a center of scholar activism. The purpose of public sociology is to collaborate with historically exploited and oppressed communities to guide policy and social movement activism to create solutions to societal problems (Katz-Fishman and Scott 2006). The surge of interest in public sociology within the discipline has attracted students and faculty to the Department because of its legacy of service to the community.

2016 Department of Sociology and Criminology Open House Guest Speakers. Left to right: Dr. Samuel Ndubuisi, Health Statistician with DHHS (Department Alum); Dr. Judy Lubin, President of Public Square Communications (Department Alum); Dr. Ralph Gomes, Professor of Sociology. Credit: Britany Gatewood, PhD. 2016.

Dedication to public sociology and researching Black social life extended to various events and projects hosted by the Department. To examine the racial shifts due to the election of President Obama, faculty and students from across Howard University created a polling center to assess Black voters’ perception of the presidential election in 2016. Dr. Terri Adams, who will later serve as chair of the Department, led the polling center along with sociology doctoral students. Over 40 student callers contacted individuals who self-identified as Black or African American to discuss topics on voter registration, political affiliations, political issues facing Black America, racism, income inequality, and social justice. Public sociology continued to permeate the Department’s programming, and the inaugural Community Engagement Open House was hosted in 2016. This annual event brings together community organizations, students, and the broader community.

The Legacy of the Mecca

The Department of Sociology and Criminology at Howard University has made numerous contributions to the discipline and American society. The accomplishments of faculty and students include articles, award-winning books, distinguished career awards, coveted fellowships, and government contracts and grants. Organizations, including the Thurgood Marshall College Fund, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Ford Foundation, have supported research that has ranged from inequalities within the criminal justice system to the impacts of natural disasters on communities of color. Since the Department’s inception, the graduate program has produced over 100 M.A. degrees and over 150 Ph.Ds., with a majority being Black scholars. Graduates have gone on to positions in the government, including for the U.S. Census Bureau and Center for Disease Control, and have taken faculty positions in academic institutions nationally and internationally.

HU Inside Out Program at the DC Department of Corrections. Dr. Bahiyyah Muhammad, Assistant Professor. Credit: Muntaquim Muhammad.

The Department continues the legacy of Dr. Kelly Miller. For over 100 years, “How will you use this knowledge to help your community?” has been a common theme throughout the scholarship, research, mentorship, and teaching at the Mecca. The undergraduate and graduate curriculum continues to center social inequality and critical discourse with an integration of scholar activism and public sociology. Centering inequality, the Black experience, and service has distinguished Howard from other sociology departments. The sentiments of current students attest to the environment that has been cultivated for over 100 years.

Impacts of Hurricanes Irma and Maria on the residents and first responders of St. Thomas. Left to right: Cassandra Jean, Ph.D. student; University of Virgin Island Representative; Dr. Terri Adams Fuller, Chair. Source: Cassandra Jean, 2019.

“Howard has curated a space for critical dialogue around the intersections of race, class, oppression, and social institutions.” – Cassandra Jean, 3rd year Ph.D. student

“Howard University creates a community for young Black scholars, while bringing a diverse culture to the environment. I personally have gained a wealth of knowledge and connections with Black educators with different backgrounds and concentrations who are determined to educate others and bring awareness to the injustices within America.” – Sydni Turner, 2nd year M.A. student

“Howard has always been the helm of Black thought, critical and revolutionary ideology, and activism. The Department has operated this way historically and continues to embed these ideals for current and future scholars. Every professor centers the Black voice, when oftentimes within sociology, our voice is left unheard. Howard teaches us not only to highlight our perspectives but its significance and its power.”- Anthony Jackson, 5th year Ph.D. Candidate

Looking Towards the Future

The Department has had profound influences on the discipline of sociology and in local, national, and international communities. Miller founded the Department during the Jim Crow era, a time where there were few opportunities for Black scholars. Its faculty and students resisted oppression and segregation during the Civil Rights Movement. Howard continues to endure through the current, intensified marginalization of HBCUs. The scholarship produced out of the Department continues to be innovative and give voice to the Black community by Black scholars. In the years to come, the department will continue Miller and Frazier’s legacy by centering social inequality, uplifting the community, and by bringing truth and service to the discipline.

ASA Annual Conference, New York, 2019. Left to right: Dr. Walda Katz-Fishman, Professor; Marie Plaisime, Ph.D. student; Dr. Joyce Ladner, former chair; Dr. Britany Gatewood, department alum; Shannell Thomas, Ph.D. student; Anas Askar, Ph.D. student; Tia Dickerson, Ph.D. Student.

Source: Britany Gatewood, PhD, 2019.

“The most important part of the continuing legacy of the Sociology and Criminology Department at Howard is to fight to keep, in a new moment, that vision of a transformative sociology for the people who are most marginalized, oppressed, and most exploited. Howard is where this marginalized section of society sends its intellectuals to be educated.”

– Dr. Walda Katz-Fishman, Professor of Sociology.

References

Alexander, Michelle. 2012. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York, NY: The New Press.

Davis, Kiara. 2019. “One Hundred Years of Sociology at Howard University by Kiara Davis on Prezi.” Retrieved April 2, 2020 (https://prezi.com/-7daf9eztnaf/one-hundred-years-of-sociology-at-howard-university/?utm_campaign=share&utm_medium=copy).

Dingwall, Robert, Brigitte Nerlich, and Samantha Hillyard. 2003. “Biological Determinism and Symbolic Interaction: Hereditary Streams and Cultural Roads.” Symbolic Interaction 26(4):631–44.

DPAAC Staff. 2016. “Watkins, Mark Hanna.” Retrieved April 14, 2020 (http://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu/262).

Frazier, Franklin E. 1949. “Race Contacts and the Social Structure.” American Sociological Review 14(1):1–11.

Gomes, Ralph C. 2018. The Expansion of Graduate Studies in Sociology During the Decade of the 1970s. Washington, D.C. Unpublished Manuscript.

Howard University. 2020. “Department of Sociology and Criminology.” Retrieved April 14, 2020 (https://sociologyandcriminology.howard.edu/).

Jarmon, Charles. 2003. “Sociology at Howard University: From E. Franklin Frazier and Beyond.” Teaching Sociology 31(4):366–74.

Jarmon, Charles. 2013. “E. Franklin Frazier’s Sociology of Race and Class in Black America.” Black Scholar 43(1–2):89–102.

Katz-Fishman, Walda and Jerome Scott. 2006. “A Movement Rising: Consciousness, Vision, and Strategy from the Bottom Up.” Pp. 69–81 in Public Sociologies Reader, edited by J. Blau and K. E. Iyall Smith. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Miller, Eleanor M. and Carrie Yang Costello. 2001. “The Limits of Biological Determinism.” American Sociological Review 66(4):592–98.

Office for Civil Rights. 1991. Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Higher Education Desegregation. Washington: US Department of Education (ED).

Platt, Anthony M. 1991. E. Franklin Frazier Reconsidered. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Williams, Linda Faye. 2003. The Constraint of Race: Legacies of White Skin Privilege in America. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Thank you.

I began Howard’s Ph.D. program in sociology soon after Dr. Gomes created it. Actually, Dr. Gomes was one of my advisors. Dr. James Scott served on my dissertation committee as well. For so many reasons, I felt blessed to have found such a welcoming, supportive, and intellectually stimulating environment. I got my Ph.D. in 1983.

I was surrounded by sociologists who had high expectations but by the same token were there for me whenever I needed advice and encouragement. As a white male who was a full-time professor of sociology at Baltimore City Community College and a father who put family first, Howard was a great fit for me. My experiences deepened my interest in diversity and race relations in particular. As an author, I have drawn on my education at HU for the last four decades (see diversityconsciousness.com).