By Paula England and Jessie Ford

What is going on in today’s heterosexual college scene, which features both casual “hookups” and exclusive relationships? How does gender structure students’ experiences? We’ll give you an overview, using data from the Online College Survey of Social Life (OCSLS) led by Paula England. This survey was taken online by over 20,000 students from 21 four-year colleges and universities between 2005 and 2011. We limit our analysis to those who said they are heterosexual.

An Overview of What’s Happening

Most students are involved in both exclusive relationships and hooking up at some point during their time in college. As students use the term “hookup,” it generally means that there was no formal, pre-arranged date, but two people met at a party, or in the dorm, and something sexual happened. Hookups can entail anything from just making out to intercourse.

The survey asked students who said they had ever hooked up while at college to provide details about their most recent hookup. It provided a list of sexual behaviors; they checked all that applied. We found that 40 percent of hookups involved intercourse, and 35 percent involved no more than making out and some nongenital touching. The rest involved oral sex and/or hand-genital touching.

Who Initiates Dates, Relationships, and Sex?

Behavior in both hookups and relationships is structured by gender. For example, many women aim for male-traditional careers, but few ever ask a man on a date. Only 12 percent of students reporting on their most recent date said that the woman had asked the man out. A large majority of both men and women report that they think it is okay for women to ask men out—it just doesn’t happen much. Reports of who initiated the date or the talk defining the relationship match up quite closely.

How about initiating sex in hookups? Male initiation is more common than female initiation. But the size of the gender difference in initiation is unclear because men and women report things differently. Men attribute initiation to themselves than to the woman, but not by a large margin.

By contrast, women are much more likely to attribute initiation to the man than to themselves. We suspect that women are reluctant to initiate or to claim doing so in hookups because of the double standard of sexuality, that is, because women are judged more harshly for engaging in casual sex than men are.

Who Has Orgasms in Hookups and Relationships?

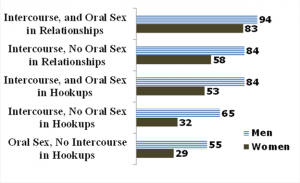

When we analyze gender inequality in the workplace, we usually focus on the sex gap in pay. In the casual sex of hookups, we could see sexual pleasure as an analogous outcome measure. One available measure of pleasure is whether the student reported that she or he had an orgasm. Students were asked whether they had an orgasm on their last hookup, and also on the last time in their most recent relationship (of at least six months) when they did something sexual beyond just kissing with their partner. The figure below shows the orgasm gap in various types of hookups and in relationships.

Percent of Men and Women Reporting an Orgasm in Recent Hookup and Relationship

Note: oral sex refers to whether the student reporting on his or her own orgasm received oral sex. Data limited to students identifying as heterosexual in male/female events.

We conclude several things from the graph: (1) There is a large gender gap in orgasms in hookups. (2) A gender gap in orgasms also occurs in relationship sex, but it is much smaller than in hookups. (3) Both women and men are more likely to have an orgasm in a relationship (given the same sexual behavior). Thus suggests that relationship-specific practice, caring for the partner, both matter for both men and women’s pleasure. (4) When couples have intercourse, both men and women are more likely to orgasm if they received oral sex, and this is especially true for women.

In addition to being asked about whether they had an orgasm in hookups, students were asked if their partner orgasmed. What is striking is how much men appear to overstate their partners’ orgasms. This may be because women fake orgasms to make men feel better, and men are misled by this; we learned in qualitative interviews that some women do this, but don’t know how prevalent it is. It is also possible that men simply don’t know and make an exaggerated assessment.

If women had an orgasm, they are much more likely to report that they enjoyed the hookup. However, despite the gender inequality in orgasm, women report almost the same degree of overall enjoyment of their hookups as men report.

Conclusions and Speculations: Gender in the College Sexual Scene

Men are more likely to initiate dates, sexual behavior, and exclusive relationships. Women may feel uncomfortable initiating or claiming initiation for sex in hookups because of the double standard of sexuality, under which they are judged more harshly than men for casual sex. Hookup sex leads to an orgasm much more often for men than women; this gender gap in orgasm is greater in casual than relational sex. We speculate that men’s lack of concern for their partner’s orgasm in hookups flows from holding the double standard that gives them permission for casual sex but leads them to look down on their partners for the same behavior.

We suggest the following.

First, other research shows that gender equality in careers is enhanced when marriage and childbearing are delayed until later ages. To the extent that hooking up rather than early involvement in relationships delays marriage and childbearing, it contributes to gender equality.

Second, an alternative to a series of hookups in college could be a series of a few extended monogamous relationships. Because we find that women orgasm more and report more enjoyment in relationship sex than hookup sex, a change from hookups to relationships would improve gender equality in sexual pleasure. One question is whether this shift could occur without encouraging earlier marriage, which, as mentioned, is bad for gender equality in careers.

Third, because we speculate that it is men’s belief in the double standard that leads them to fail to prioritize their hookup partners’ pleasure because they feel some disrespect for them, it follows that if the double standard could be changed, gender equality in sexual pleasure might be achieved within the hookup context.

Note:

This article summarizes a talk presented by ASA President Paula England to DCSS in November 2014. If you are interested in using the OCSLS data, contact Paula England at pengland@nyu.edu.

For published analyses using the OCSLS data, see:

- Armstrong, Elizabeth, Paula England, and Alison Fogarty. 2012. “Accounting for Women’s Orgasm and Sexual Enjoyment in College Hookups and Relationships.” American Sociological Review 77(3): 435–462.

- Bearak, Jonathan Marc. 2014. “Casual Contraception in Casual Sex: Life-Cycle Change in Undergraduates’ Sexual Behavior in Hookups.” Social Forces 93: 483-513.

- England, Paula and Jonathan Marc Bearak. 2014. “The Sexual Double Standard and Gender Differences in Attitudes Toward Casual Sex among U.S. University Students.” Demographic Research 30, 46:1327-1338.

- England, Paula, Emily Fitzgibbons Shafer, and Alison C. K. Fogarty. 2012. “Hooking Up and Forming Romantic Relationships on Today’s College Campuses.” Pp. 559-572 in The Gendered Society Reader, Fifth Edition, edited by Michael Kimmel and Amy Aronson. New York: Oxford University Press.