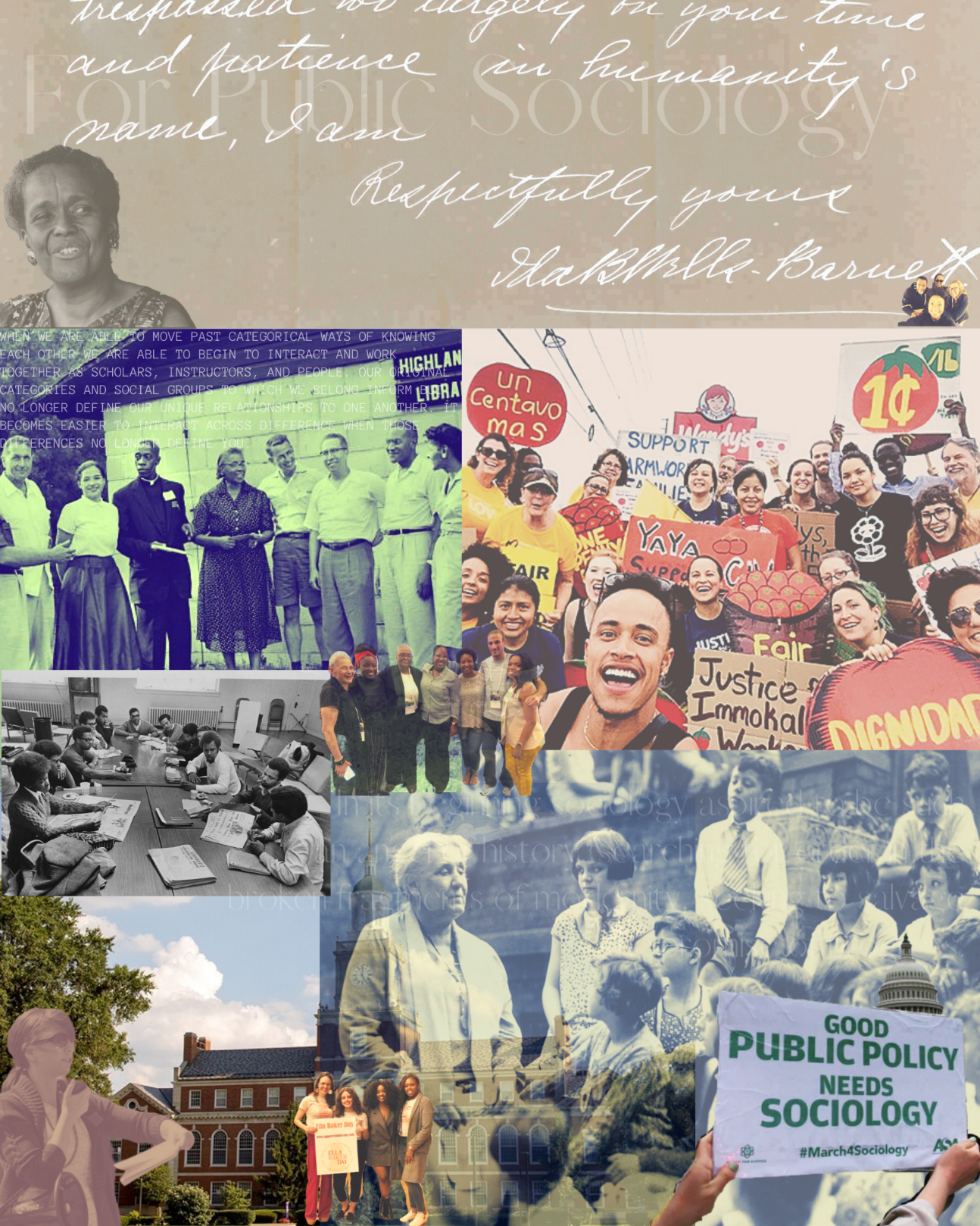

In 2004, Burawoy gave his presidential address, “For Public Sociology,” to the American Sociological Association causing a stir within the discipline, its effects still felt today in graduate seminars and in debates about the current state and future of sociology. In one speech, Burawoy reinvigorated the historical promise of imagining sociology as a discipline that can both explain society and work towards a more just world. In the wake of his address, debates arose around the meaning and purpose of public sociology (Clawson Sussman, Misra, et. al. 2007).

What public sociology is, what it looks like, are questions that have led to vigorous thought experimentation but little noticeable change in the discipline. Burawoy’s call may have reinvigorated the sociological debate about discourse with diverse publics, but it fell short of suggesting sociology should look to its own history to re-learn how to engage with many publics and, more importantly, to embrace worlds outside of the academy, to learn and to solve problems together.

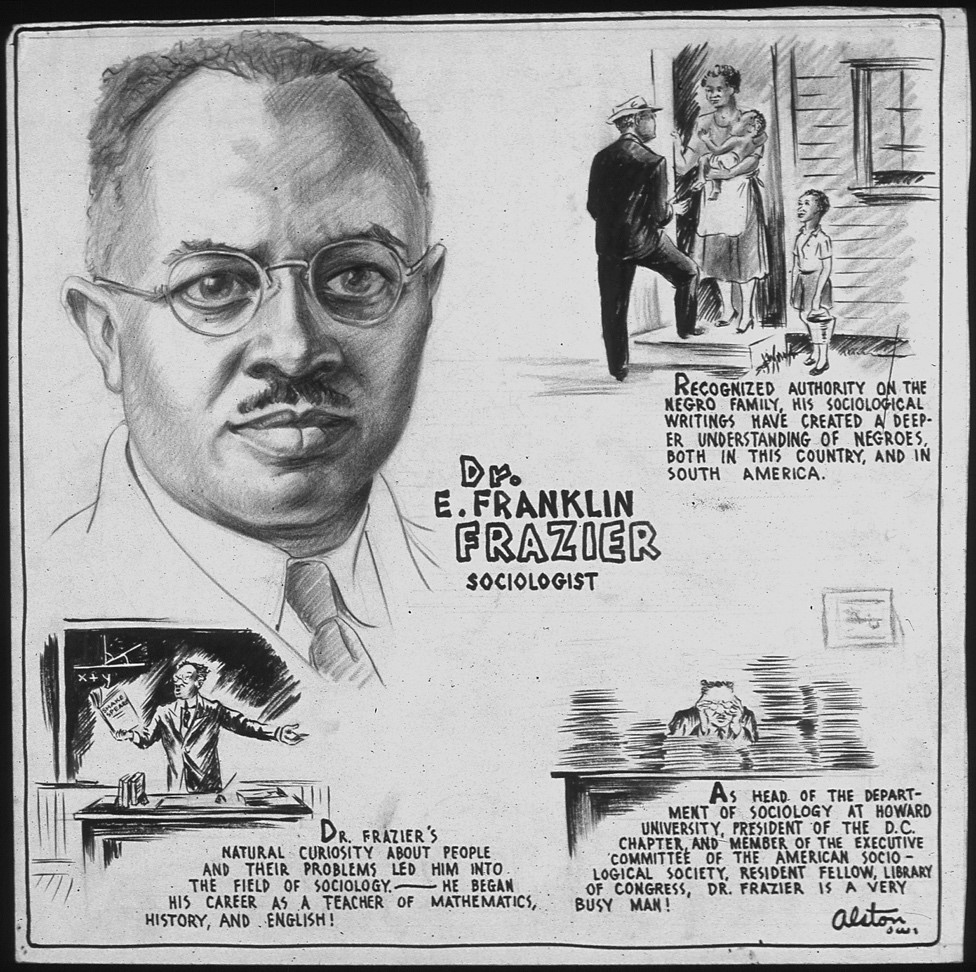

Solving problems together through collaboration between scholars and publics was a central feature of the sociological research community long before Burawoy gave his address. The systematic study of structural forces and their impact on human thriving were employed among public intellectuals (though not always sociologists by training), among the likes of Jane Addams, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Anna Julia Cooper, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, W.E.B. Du Bois, Paolo Freire, Orlando Fals Borda, Septima Clark, Ella Baker, Myles and Frances Horton, and many unsung scholars who have yet to be admitted to the canon among the “greats.”

One approach to social science research, Participatory Action Research (PAR)1, a collaborative, solutions-based approach does as Mills (2000) suggested sociology should; it connects personal troubles with public issues. It is also an orientation toward deep engagement with publics and is intended to bring about social transformation, liberation, conscienziacion (to free oneself — Freire 1970) to create a more humane and just world. Rather than simply engaging in dialogue with diverse publics, as Burawoy suggested, implementing a PAR approach requires researchers working alongside ordinary people, utilizing social science research to produce useful and valid findings while at the same time alleviating (or reversing) harms.

This article describes the PAR approach, an orientation for “doing” public sociology in the historical tradition of the people mentioned earlier and in answering Burawoy’s call for more engagement with diverse publics. First, we discuss participatory research as an approach with theoretical foundations. Next, we describe the three pillars, which are the core to this approach, and the deep relations and trust necessary to do this work successfully. We then provide a set of considerations for increasing participation and engaging communities across research phases utilizing the PAR approach. Finally, we provide links to PAR approach resources, journals, professional associations, and suggested reading to learn more.

Participatory Action Research Approach and its Theoretical Roots

PAR approaches are becoming better known in sociology and other disciplinary fields. However, there remains confusion and misperceptions about what it is, and what it is not. This is partly due to the interdisciplinary theoretical underpinnings of participatory research, how it has emerged and evolved across disciplines, and its focus (e.g., transformational, systems change). PAR is an approach or orientation to how research is conducted with a set of action goals, as opposed to a research method.

For illustration, we will describe key elements of a better-known comparison case, a more traditional positivist approach founded by early sociologist Auguste Comte, generating universal laws for the social world that are validated by empirical data, in a mode similar to natural science (Turner 2001). To do so, key principles guide data collection strategies. Two of the most common are: first, an emphasis on reliability, using instruments that generate the same results each time they are used; and second, a belief in objectivity in which “researchers should remain distanced from what they study so findings depend on the nature of what is studied rather than on the personality, beliefs, and values of the researcher” (Payne and Payne 2004: 152).

When employing this traditional social science approach, it is most common to use quantitative research methods, like surveys, experiments, and secondary data analysis. Likewise, PAR is an approach rooted in critical theory and from various reactions to the German philosopher, Hegel. For critics, empiricism was too simplistic and mechanistic to build critical analysis or understand the nuances and patterns of human life. Building on Hegel’s work, Karl Marx and other canonical sociological theorists, such as those in the Frankfurt School and Weber, to name a few, continued developing theoretical approaches to distinguish the social sciences from natural science, to understand human behavior from the perspective of communities and individuals, and to improve material and social conditions.

In the 20th century, a small number of social theorists and activists in the U.S. and elsewhere continued to build on these approaches, and more importantly, began to apply these theories to work in and alongside communities to improve living conditions. Given the intent to understand lived experiences rather than formulation of social laws, research methods often employed are qualitative, including interviews, focus groups, ethnography, participant observation, and critical discourse analysis.

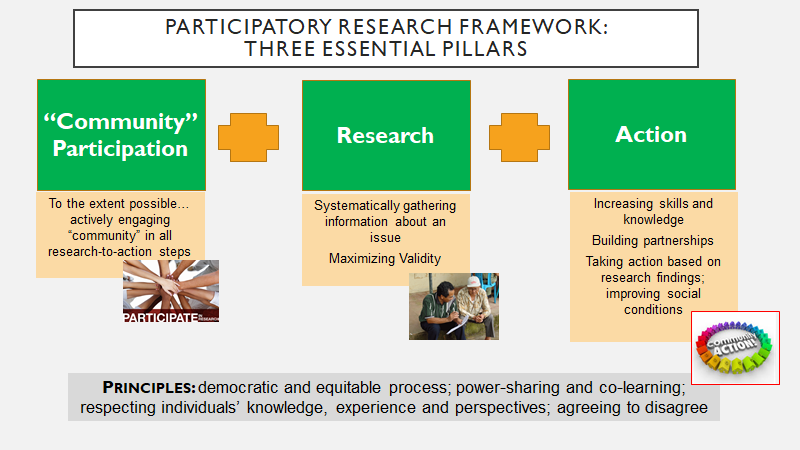

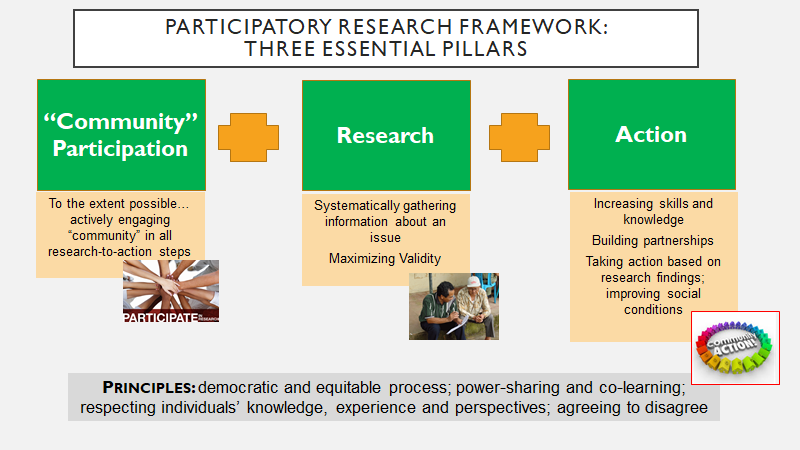

Unlike traditional sociology, a PAR approach is an example of critical sociological scholarship that focuses on knowledge building and liberation and actively seeks to alleviate suffering through action. PAR researchers choose not to “ignore the oppressive values and discriminatory practices of the status quo” (Feagin and Vera 2008). In effect, the orientation not only enables the production of trustworthy scholarship, but also allows the researcher to “take sides” against that which causes harm to the communities we work with. In addition to the production of new knowledge, PAR is guided by several principles, including: 1) PAR is a democratic and equitable process; 2) power-sharing and co-learning are crucial to successful implementation; 3) respect for individuals’ knowledge, experience, and perspectives is key, and 4) agreeing to disagree is expected.

In our view, three pillars are essential to a participatory research approach: 1) active engagement of the community, ideally in the entire research-to-action process, 2) using a research design or methods to collect data systematically, and 3) using the findings to generate action plans and increase community engagement to improve social conditions.

These three pillars working together make this approach distinct from traditional social science and moves it beyond elements of critical theory to not just explain the social world but work with publics to transform it. Putting it simply, if researchers conduct a study in a community because they are interested in explaining a particular phenomenon (e.g., redlining, lack of public services, disproportionate impact of the coronavirus), and only engage the community to obtain feedback as opposed to working in partnership with the community without direct action, this would still be an example of a traditional research approach regardless of the theoretical underpinnings driving the study.

Social scientists working with communities and stakeholders in a research-to-action process has benefits for the research and the communities. Individuals with lived experience bring local expertise, have local networks they can engage, and can help bridge the divide and build trust between the researcher and the community. Their knowledge and perspectives contribute to crafting research questions and instruments that represent the issues or phenomenon that the study seeks to understand and measure, and therefore we argue, maximizes validity. In this research approach, trained individuals with lived experience and local expertise contributing the entire research-to-action process is considered a benefit to the process, not a lapse in objectivity.

Communities build capacity as they conduct PAR including how to build knowledge around an issue, research ethics and confidentiality, data collection, analysis, and how to translate findings and present those findings to their community so they are understood and can be utilized outside of the academy. Because of their methodological and theoretical training, and general interests in understanding power dynamics, sociologists have an important role to play in participatory research. Like any research study, it is important to know how to develop a defensible research design and at the same time know how to obtain the type of data necessary for the community to make evidence-based choices to seek the change they desire.

Despite our skills and training, many sociologists have little exposure to PAR. Our intent is to describe features of the PAR approach to not only make an argument for why PAR is an opportunity to “do” public sociology by working alongside people with lived experience but also to pique the interest of sociologists to do this work. The sections that follow are instructive for this second purpose.

Considerations for Engaging Communities Across Research Phases Utilizing the PAR Approach

Given that the underlying principles and goals of “doing” participatory research are to address power dynamics, through trust, community and relationship building, how do you engage communities to conduct PAR? Engagement and collaboration at each stage of the research-to-action process is essential to meeting these goals and is one of the distinguishing features between traditional and participatory research approaches. Below are some suggestions on how researchers could think of working with the community to create these opportunities.

Community Building

Fruitful implementation of PAR requires building authentic relationships. This often begins with connecting with community organizers, non-profits, or other community-based groups with an interest in understanding issues and harms systematically in order to alleviate them through self-directed action. In practice, this may mean many conversations, explaining the approach, its benefits, and working to counter mistrust of research(ers). Be prepared to listen and put in work you may feel is unrelated to research. In addition, community building with the broader community includes thinking about how to reach out to more community networks and stakeholders at each step. Gathering information and feedback early and often from multiple stakeholders will bring more interested parties to the table for action planning and implementation which is key to successful social change.

Community Building with a Research Team

Conducting an authentic participatory research study requires forming partnerships between individuals with diverse knowledge–a research team can be composed of a researcher, community members, and other stakeholders. This type of collaboration means working with people who may have different lived experience, and thus requires team building, flexibility, and respect for different types of knowledge. Crucial is knowing when to step in as the leader and facilitator and when to step back.

As the research team is established, collaboration to understand community issues follows. It is also important to establish roles, determine the type of expertise needed, devise shared principles, conduct skills and cultural asset mapping, resolve issues around representation (is there agreement that the right people are “at the table?”), and deal with power differentials.

Source: Andrea Robles.

PAR is intended to build capacity in the community, yet participants are often the same people in our society who are un(der)compensated for their labor (including emotional labor). Consequently, logistical issues like recruitment and remuneration for the labor, transportation, and meals for participants are important during this phase. There should be a commitment to regular gatherings for training, reflection, and team building that are agreed to during the initial phase as well.

Research Design and Execution

By now, you may be wondering what is the role of the PAR facilitator (that’s you, the “researcher”)? You may facilitate a process to develop your study’s research question(s) with your team. They may emerge from an existing community need or interest, a workshop, or through a more elaborate six-step approach like the SEED method devised by Zimmerman (2020).

A trained sociologist has a toolbox of qualitative and quantitative research methods they can employ, teach, and implement to collect data systematically and ethically, and can understand how to adapt methods and instruments to be culturally appropriate. You may teach research skills including confidentiality and protection of human subjects, engage in discussions about the advantages and disadvantages of different types of traditional and nontraditional research methods, and practice by role playing.

Once the team understands the methods, you may facilitate a process or conduct workshops about choosing the most appropriate research methods to answer the study’s research question given the resources and develop instruments and data collection protocols. Research methodology development requires time for reflection, dialogue, circling back to topics as needed so the team (you included) feels knowledgeable, and comfortable to do the data gathering work. Common methods used in participatory research include (but are not limited to):

1. Surveys, focus groups, one-on-one interviews2: Research teams may decide to use these more traditional social science methodologies. PAR often employs diagramming, dot-voting, and other methods of expression to use during interviews and focus groups to elicit responses for less talkative people or people from diverse linguistic communities.

2. Community mapping, transect walks: This is a systematic walk along a defined path with local people, typically a group, who will collectively: observe, ask, listen, and look at their surroundings. These are excellent techniques to open opportunities for conversation. Data is often represented with maps. Also conducted by viewing Google maps to analyze change over time (i.e., neighborhood development and gentrification).

3. Photovoice (or photo elicitation): Community researchers take photographs that illustrate issue(s) of interest and discuss them in a group setting, specifically, how the photos illustrate the issue(s), their community’s needs, assets, connections to structural forces. This method increases visibility of those often invisible, is a less intimidating way to share feelings, increases participants ability to reflect, helps produce a clearer understanding of issues, and produces compelling photographic records for political/local change-makers (Wang and Burris 1997; Clark-Ibáñez 2004).

4. Q-sort: This method helps the research team to understand multiple perspectives on an issue by ranking and sorting a series of statements (or photographs) developed by the research team. It brings to light many perspectives with a low barrier to participation and does not require similar understandings or orientations to an issue. The team develops the data to be analyzed, recruits participants, conducts the sorting activity (from least to most preference with a roughly normal distribution of data), and conducts analysis/interpretation. This method does require some software expertise which can be acquired by a team or other expert participant (van Exel and de Graaf 2005).

5. Oral histories, storytelling, and testimonios3: Research team members learn how to prepare an interview guide with questions and probes for follow-up questions to solicit depth and detail based on the research question(s). Then they recruit, schedule, and conduct the interviews. Training may be necessary for record-keeping procedures, interview research and preparation, interview setting, use of the equipment, interviewing techniques, transcription, coding, and theme building.

Collaborative Data Analysis and Interpretation

As with any social science research, once the data has been collected, it must be analyzed. The researcher needs to spend time teaching, mentoring and reviewing the work. It is exciting for the entire team to discuss and interpret the findings they have devoted so much time to learn. However, unlike a sole researcher’s work there may be multiple interpretations of the data and decision making on the form findings may take. This requires creating openings for honest discussion, debate, and ultimately might take practicing the principle of “agreeing to disagree.”

Presenting Findings and Developing Action Plans

Presenting findings and developing action plans with the team and other stakeholders is part of an action-reflection cycle. The team with expert knowledge about the community can decide on how best to present the results themselves in ways that can be understood, utilized, and exciting for multiple audiences who are not only interested in learning about the issue investigated but also enthusiastic to be part of social transformation.

An important part of action planning is stakeholders committing to how to use the findings to improve local conditions. During presentations, audiences can provide feedback on next steps and engage in action planning. An action plan may be internal to an organization or externally facing (i.e., to policy makers, city councils, written as a newspaper article, etc.). Reports are traditional ways to present information but there are also other creative methods such as presenting the findings through poetry, theater, songwriting, or memory books, in community meetings or during data walks to engage the public further.

Evaluating

Can PAR work be evaluated? Yes, this work can be evaluated using traditional or participatory strategies like Ripple Effects Mapping (Chazdon, Emery, Hansen, et al. 2017). One advantage of this evaluation technique is that it captures both the intended effects of the work but also the unintended effects that are often left out of traditional evaluation methods.

Conclusion

PAR is but one example of an approach to “doing” public sociology that extends beyond Burawoy’s call for discourse with diverse communities. It is a return to the historical roots of sociology to re-learn to embrace publics and solve social problems together. It extends beyond traditional sociological efforts to understand and explain the social world regardless of whether it is to establish social laws or learn the nuances of human life. This approach is unapologetically about bringing people into a research-to-action process who have lived experience, their own perspectives, beliefs, and are interested in using knowledge to make positive social change in their respective communities.

Like traditional research, PAR may lead to peer-reviewed publications, books, conference presentations, and policy or position papers. Unlike much traditional research, this work may also lead to deep and long commitment to communities, skill development and empowerment of participants, and celebration! This approach may not be for everyone. However, the benefits, skills and knowledge gained for all team members, the enjoyment of working with an enthusiastic team, and the opportunity to produce knowledge that is liberating for us and the communities we work with can reconnect us with our disciplinary history.

Notes

1. We are referring to the approach as Participatory Action Research throughout this article. More transformational but no less collaborative than other closely related approaches called participatory research, action research, Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR). See suggested readings for more discussion on distinctions among them.

2. These methods are known to most sociologists and will not be described further here.

3. Described as narraciones de urgencia (emergency or urgent narratives); a means to bear witness to injustices through spoken or written word (Caxaj, 2015).

References/Suggested Reading

Bergold, J. & Thomas, S. (2012). Participatory Research Methods: A Methodological Approach in Motion. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13 (1). Art. 30, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1201302

Caxaj, C.S. (2015). Indigenous Storytelling and Participatory Action Research: Allies Toward Decolonization? Reflections from the Peoples’ International Health Tribunal. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 2, Jan-Dec 2, doi: 10.1177/2333393615580764

Clark-Ibáñez, M. (2004). Framing the social world with photo-elicitation interviews. American Behavioral Scientist. 2004;47:1507–1527.

Clawson, D., Sussman, R. Misra, J., Gerstel, N., Stokes, R., Anderton, D.L., eds. (2007). Public Sociology: Fifteen Eminent Sociologists Debate Politics and the Profession in the Twenty-first Century. University of California Press: Berkeley, CA.

Fals Borda, O. (1998). People’s Participation: Challenges Ahead. New York and London: Apex Press and Intermediate Technology Publications

Feagin, J. & Vera (2008). Liberation Sociology, 2nd ed. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed, New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group

Israel, B., Eng, E., Schulz, A.J., Parker, E.A. (eds) (2005). Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health, San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Jason, L A., Keys, C. B., Suarez-Balcazar, Y, Taylor, R.R., and Davis, M.I. (eds.) (2004). Participatory Community Research: Theories and Methods in Action, Washington DC: American Psychological Association

Kindon, S., Rachel Pain, and Mike Kesby. (2007). Participatory Action Research Approaches and Methods: Connecting people, participation, and place. New York: Routledge Studies in Human Geography.

Krishnaswamy, A. (2004). Participatory Research: Strategies and Tools. Practitioner: Newsletter of the National Network of Forest Practitioners, 22: 17-22.

Mills, C.W. (2000 [1959]). The Sociological Imagination, 40th Anniversary Edition. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK.

Minkler, M. and Wallerstein, N. (eds.) (2008). Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes, 2nd Edition. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley and Sons; Reason, P. and Bradbury, H. (eds.) (2001) Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications Inc.

Payne, G. and Payne, J. (2004). Key Concepts in Social Research. “Objectivity”, Pp. 152-156. Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA.

Pink, Sara. (2007). “Photography in Ethnography.” Doing Visual Sociology. Sage Publications.

Richie, Donald. (2003). Doing Oral History: Using Interviews to Uncover the Past and Preserve it for the Future. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Stringer, E (1999). Action Research, 2nd edition, Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications Inc.

Turner, J.H. (2001). International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Sciences, First Edition. Elsevier: New York, NY.

van Exel, J., & de Graaf, G. (2005). Q methodology: A sneak preview. Retrieved from website: https://qmethodblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/qmethodologyasneakpreviewreferenceupdate.pdf

Wang, C. and Burris, M. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 23(3), 369-387.

Yosso, Tara J. (2005). “Whose Culture Has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth.” Race Ethnicity and Education 8:69‐91.

Zimmerman, Emily B. (2020). Researching Health Together: Engaging Patients and Stakeholders, From Topic Identification to Policy Change. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks CA.

Resources

A Field Guide to Ripple Effect Mapping https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/190639

Center for Collaborative Action Research: http://cadres.pepperdine.edu/ccar/resources.html

Community toolbox (University of Kansas) https://ctb.ku.edu/en/toolkits

Critically-engaged Civic Learning Framework: https://adpaascu.wordpress.com/2018/02/21/campus-spotlight-moving-from-service-learning-to-critically-engaged-civic-learning-at-salem-state/

Data Walks: An Innovative Way to Share Data with Communities: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/data-walks-innovative-way-share-data-communities

Developing and Sustaining CBPR Partnerships: Skill-Building Curriculum, University of Washington https://depts.washington.edu/ccph/cbpr/

FAO — Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations http://www.fao.org/3/ad424e/ad424e03.htm

Institute for Community Research: https://icrweb.org/

Institute of Development Studies, Participatory Methods https://wwwparticipatorymethods.org/

PhotoVoice Methodology Guide: http://www.pwhce.ca/photovoice/pdf/Photovoice_Manual.pdf

Rapid Rural Appraisal and Participatory Rural Appraisal https://www.crs.org/sites/default/files/tools-research/rapid-rural-appraisal-and-participatory-rural-appraisal.pdf

SEED Method Toolkit: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B4pFpU3fdpexbzkzQmNqb2o4NTQ/view

The Public Science Project: https://publicscienceproject.org/

Youth-Led Participatory Action Research (YPAR) Hub http://yparhub.berkeley.edu/

Journals

Action Research: https://journals.sagepub.com/home/arj

Educational Action Research: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/reac20

International Journal of Qualitative Methods: https://journals.sagepub.com/home/ijq

Participatory Design: http://pdcproceedings.org/index.html

Qualitative Inquiry: https://journals.sagepub.com/home/qix

Locate more at: http://participatoryresearch.web.unc.edu/journals-for-participatory-research/

Professional Associations

Action Research Network of the Americas (ARNA): https://arnawebsite.org/

Participatory Research in Asia: https://www.pria.org/

Action Learning, Action Research Association: https://www.alarassociation.org/

International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (ICPHR): http://www.icphr.org/

By Melissa Gouge and Andrea Robles

Return to May 2020 Issue