On January 2, 2020, The Sociologist (TS) interviewed Dr. Joe R. Feagin, Distinguished Professor in sociology at Texas A & M University. Professor Feagin has done much internationally recognized research on U.S. racism, sexism, and urban political economy issues. He has written 73 scholarly books and 200-plus scholarly articles. His books include Systemic Racism (Routledge 2006); Liberation Sociology (3rd ed., Paradigm 2014); White Party, White Government (Routledge 2012); The White Racial Frame (2nd ed., Routledge 2013); Latinos Facing Racism (Routledge 2014); How Blacks Built America (Routledge 2015); Elite White Men Ruling (Routledge, 2017); Racist America (4th ed., Routledge 2018); and Rethinking Diversity Frameworks in Higher Education (2020). He is the recipient of the 2012 Soka Gakkai International-USA Social Justice Award, the 2013 American Association for Affirmative Action’s Arthur Fletcher Lifetime Achievement Award, and three major American Sociological Association awards: W. E. B. Du Bois Career of Distinguished Scholarship Award, the Cox-Johnson-Frazier Award (for research in the African American scholarly tradition), and the Public Understanding of Sociology Award. He was the 1999-2000 president of the American Sociological Association.

TS: What are the most important insights you can share from your distinguished career?

Joe Feagin: Probably the most important one is in regard to sociological research and analysis on the deeper realities of highly oppressive societies like the United States. Sociology as a discipline has probably done more to uncover the surface cover-ups and concealing of the underlying realities of this country than any other academic discipline. At least, a critical progressive stream in sociological research and analysis has done that. But too much mainstream sociology, especially since the 1930s or so, has moved in the direction of instrumental-positivism and emphasized statistical methods, and focused on too narrow subjects so that people can get grants from mainstream grant agencies.

I think the main insight I have gained over the years from my own research, and the critical research of many other sociologists, is just how deeply and foundationally oppressive this country is, in terms of systemic racism, systemic classism, systemic sexism/heterosexism. We have very deep foundational realities of oppression that are covered up regularly by the mainstream media, by churches, by political and educational institutions, and by other societal means that elite white men at the top of society generally use to maintain oppression today.

TS: Did you say churches, as in religious institutions?

Joe Feagin: Yes. The original intellectuals in this country—when you go back to the 1600s when slavery was being built into our country—were mostly clergymen. Jonathan Edwards, for example, the famous evangelical 17th century preacher, and many others like him, worked to rationalize slavery. And they really started the broad white racial framing I write a lot about, which on the one hand sees white people as superior and virtuous, and on the other hand views black Americans and Native Americans as inferior racially and unvirtuous. They often framed this thinking in Christian religious terms, even before there were explicit “race” categories during the 1600s; early on, they preferred to talk about “uncivilized savages” referring to black people being brought as slaves and the Native Americans being killed off on the move westward.

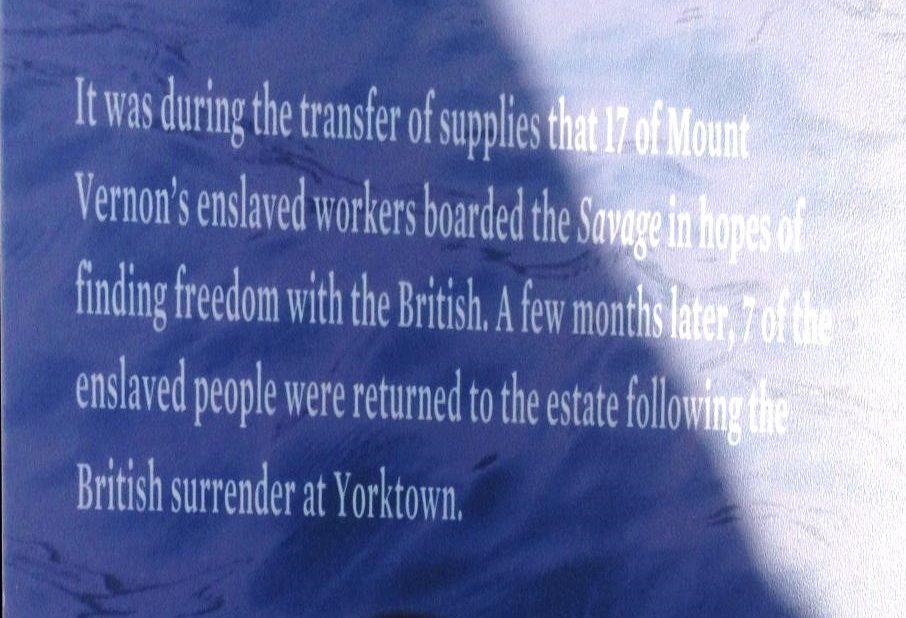

The English colonists who founded what became known as Jamestown mostly considered themselves Christians. They considered themselves civilized. They considered the people they encountered, the Native Americans, as uncivilized and un-Christian. So, the first racialized framing really was in religious terms. They considered themselves virtuous Christians, and in their minds, they were encountering unvirtuous, uncivilized others. Pretty soon, in 1619, the white colonists in Jamestown bought about 20 Africans off a Dutch-flagged pirate ship. For the first decade or so, some of those early enslaved workers could work themselves out of slavery, but after that, pretty quickly, by about 1650, most black people were enslaved, including the children of those who had come earlier. The white colonizers also bought into the old religious myth about Ham, Noah’s son—that Ham had looked upon a naked Noah and had not covered him up, and thus Ham was cursed by Noah. It is a myth developed outside the Bible. The myth makes Ham an African, and Africans, later on, as inferior and justly punished with suffering. So, being enslaved is God’s just and divine punishment. And this is just one racist narrative, one myth whites used to justify slavery that was built into that dominant white racial frame.

They also took negative words like “black” from a deeper, older European tradition, and soon they started describing Africans negatively as “black,” with ministers like Reverend Samuel Purchas making color-coded references to what soon became the “races.” So, you have the leaders of the European colonists, who were often ministers, crafting this first white racial framing of Native Americans and Africans. To some degree, they import ideas from cultures in Europe. And then you get this color-coding that is imposed on everybody by the white leadership. If you go back into English culture, the term black is used in a lot of negative ways—the devil is black for example in Christian theology, and the angels are white. Other religious ideas are used to justify the killing of Native Americans.

And now, to the question of sociology. I would say sociologists have done a lot to help us understand racial mythologizing and racism generally; we have greatly developed ideas of prejudice and stereotyping. But the reason I started talking about white racial framing is that it is a broader way of looking at this oppression in terms of the racist interpretations, racist ideology, and racist emotions as well.

The white racial framing is more than just prejudice, which is just one key feature in rationalizing oppression. You’ve also got to add into that white framing the racist interpretations, narratives, and the emotions and racist imagery.

TS: How has sociology improved our world?

Joe Feagin: I think we have created more social justice warriors than just about any other academic discipline. By the way, social justice warriors should be a good term, but it has become a very negative term used by the alternate-right, by white supremacists, by white nationalists these days. Yet, earlier critical thinker-activists like David Walker, Harriet Martineau, W. E. B. Du Bois, Anna Julia Cooper, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, and many others were social justice warriors. Thinking about sociology, it is amazing that numerous black civil rights leaders have been sociologists—they have been sociology majors, or they took a lot of sociology courses.

Dr. Martin Luther King was a sociology major at Morehouse. With a strong sociological bent, Ida B. Wells-Barnett did the first systematic study of lynching called The Red Record; she was attacked and threatened many times for her anti-lynching activities. Her printing press was destroyed because whites didn’t like what she was writing. Du Bois, one of the first black sociologists, did very important race-critical analysis. Oliver Cromwell Cox, a brilliant African American sociologist—who was trained at the Chicago School by white sociologists but became very critical of them on racial matters—wrote the first thorough and extended study of institutional and systemic racism (in his book Caste, Class and Race). I think one of the very good things sociologists have done for this society—both mainstream and more critical public sociology—is to bring the subterranean reality of racial oppression (and other oppressions) into the light of day.

TS: In terms of racial and ethnic relations, do you think the United States is moving closer to the diversity within unity ideal or are we moving closer to the American apartheid?

Joe Feagin: I would say the situation is like two trains on the same track headed toward each other. On the one hand, you have a large proportion of white Americans that has always been white nationalist—holding onto strong ideas of white supremacy, holding onto the extreme versions of the white racial frame. Generally speaking, the Republican Party, especially since the Reagan era, has become the white party in America, and it has attracted whites who hold these strong white nationalist, supremacy views.

For a while in the 1980s and 1990s, the extreme white supremacy ideas held by many whites were expressed mainly in the all-white backstage—that is, for the most part, at that time, many whites would not openly tell aggressively racist jokes or make aggressively racist statements in the more public frontstage. But since about the George H. W. Bush era, more whites have become willing to express openly and aggressively white nationalist, supremacist ideas.

This happened because of the fear of more aggressive civil rights enforcement and the browning of America. The other train coming down the same track is the non-white demography train.

The demography train will happen no matter what. It is simply that each year the white percentage of the population goes down. And since most whites are not trained to value multi-culturalism, and most whites do not have an honest understanding of white racism, and most whites do not understand what it is like to be black or Latino/a in this country, it is easy for whites to be fearful, isolated, and afraid. They believe that once people of color are in power in the country, they will do to white people, what white people have done to people of color. That is not likely. California is a very good example of the change that’s coming.

When I was a young professor there, the state was conservative, now it is one of the most liberal and progressive states. There is a minority of whites who do not mind a multiracial, multicultural society. Then you have a great many whites now becoming more openly racist. Little has really changed for the latter whites, except their openness. The demography train that is coming down the track has already arrived in California, in New York state, and in Texas.

TS: What are the problems of group identity (hyper-group identity), when it comes to fostering inter-community relations?

Joe Feagin: There’s a long conversation there. I think back on the role of sociology. Sociologists have been kind of at the forefront (together with psychology) in dealing with racial identity and ethnic identity issues. A lot of that work has focused on self-chosen identities—the identity that people choose themselves, how they see themselves. Much less research, analysis, and theory has been done on imposed identities. These are identities that are imposed on you by people with greater power and the ability to do that. Within a racial-ethnic group (and this is true of racial identity groups), there are often ethnic divisions in terms of national origin; it is certainly true for whites.

However, people of color run into the reality that white people have disproportionate power that allows them to impose racial identities. That’s the problem of identity politics in this country. Now, the most important identity politics is what we don’t talk about, it is white identity politics. That is what white nationalism is about. When whites talk negatively about U.S. identity politics in reference to people of color, they are really indirectly featuring white identity politics.

TS: Who is your hero or mentor; who has inspired you?

Joe Feagin: Sadly, I have never had very good mentors. At least, not since the 7th grade. And that was true in college and in graduate school. I think (and this might be a bit arrogant) one of the things I do well is academic mentoring; I have learned how to do that pretty well, because I have not had good mentoring. I had some partial mentoring, but rarely. At Harvard, Gordon Allport was the closest to being a mentor; he was in his last faculty years, but he helped me get some modest research funding as a student. He was a kind and generous man, and one of the founders of modern social psychology.

Most of the people who have inspired me a great deal have been scholars and scholar-activists in the black critical tradition, like Du Bois especially. When I started reading Frederick Douglass and other black critical thinkers as a graduate student and young faculty member in the 1960s—for example Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), and many others—they had a profound influence on me. The 1960s and early 1970s were a very dynamic time for critical sociologists. Lots of critical sociology analyses, a lot of it outside of mainstream sociology.

And a lot of the (especially younger) sociologists of various backgrounds were beginning to read critical analyses of racism, classism, sexism. Kwame Ture’s book with Charles Hamilton (Black Power) dealing with institutional racism had a major effect on my research. And when I got to know about and study some of the early women sociologists, like Jane Addams and Harriet Martineau, I began to understand just how systemic sexism also was in this country.

I also had a political economist friend who got me to read Karl Marx for the first time in the 1960s. When I was in graduate school taking social theory classes, Marx was a non-person. My theory class had Durkheim, Weber, but no Marx. Talcott Parsons was a towering figure then at Harvard; and George Homans was my theory professor. Neither had any use for Marxist ideas and analysis.

I had one little course on the sociology of the Soviet Union, where Marx was at least mentioned and that was the only place I encountered Marx’s ideas during my undergraduate and graduate school years. You know, that was at the tail end of severe McCarthyism, which pretty much wiped out much Marxist thinking in universities. These historical and contemporary scholarly and activist figures were not personal mentors, but they have had powerful intellectual influences on me and my research over the years.