By Patricia Lengermann and Gillian Niebrugge

In 1887, at age 29, Anna Julia Cooper arrived in Washington D.C. She would—with only a brief hiatus—live here for the rest of her long and productive life, and the structures, rhythms, and relational patterns of the city would permeate the writing and activism that made her a local prominence in her time and a significant presence in the theoretical canon of classical sociology in our own. But in 1934, when the District of Columbia Sociological Society (DCSS) held its formative meetings, Cooper, then President of Frelinghuysen University, was a non-presence, not even conspicuous by her absence.

This situation—of a blankness or vacuum about a major social theorist who developed her ideas against the backdrop of Washington, D.C.—reveals how much DCSS itself was an unwitting product of the society its members attempted to study, a society with a long and still unresolved history of racial and gender injustice. This article, part of a series on the history of sociology in the DCSS area, introduces Anna Julia Cooper with an emphasis on the ways living in Washington, D.C. influenced her social theory and her social activism.

Biography

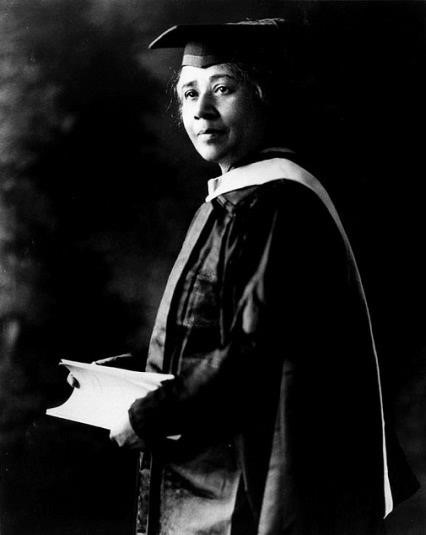

Cooper’s remarkable life is told in some detail by nearly every scholar who touches her work, e.g. Hutchinson (1981), Lemert and Bahn (1998), Lengermann and Niebrugge (1998/2007), Baker-Fletcher (1994), and Washington (1988). She was born around 1858 into slavery, in Raleigh, North Carolina, with no possessions save the love and example of her mother and her own prodigious intelligence. At every turn of her life, she faced the challenge of being both “self-supporting” and the support for many relatives. Her intelligence, coupled with a firm discipline, let her make her way through St. Augustine Normal School and Collegiate Institution, a freedmen’s school in Raleigh, to Oberlin College and on, in 1887, to a highly successful teaching career in Washington, D.C. at the prestigious “M” Street School.

During the early Washington, D.C. years, she established a formidable reputation within the African American community and beyond as a scholar, orator and community activist.

Her teaching career in Washington, D.C. was interrupted by a controversy over the course of African American education that forced her to leave the District for four years. Returning to teaching in the District in 1910, she won a kind of vindication by earning her Ph.D. from the Sorbonne in 1925 when she was 67 years old. In the 1930s, she served as President of Frelinghuysen University, a school founded on the principle of providing education and job training for what its founders termed “the unreached.”

Anna Julia Cooper’s home at 201 “T” Street N.W. Source:http://househistoryman.blogspot.com/2012/02/anna-julia-cooper-frelinghuysen.html.

She lived to see Brown v. Board of Education and the March on Washington. She died in 1964 in the stately home on “T” Street, N.W. that she had bought for herself out of a teacher’s salary in order to properly execute one of the many duties of service she assumed in her life, the raising of her deceased brother’s five orphaned grandchildren.

Social Theory

During her early years teaching in Washington, D.C. Cooper wrote what remains her major achievement in social theory, A Voice from the South, published in 1892, one year before Durkheim’s The Division of Labor in Society. Voice was critically well-received in its own day and then, as the DCSS episode shows, forgotten; it has taken the historic intersection of the Modern African American Civil Rights Movement and the Second Wave of the Women’s Movement to bring this significant work of theory once more into the academic discourse across multiple disciplines, Black Studies, Women’s Studies, philosophy, theology. In sociology the recovery, beginning with Lemert’s pioneering recognition (1995) has been slower and remains part of the “still unfinished feminist revolution.”

Four points in Voice may be of special interest in an introduction to sociologists: Cooper’s development of the concepts of standpoint and intersectionality, her outline of an American theory of conflict and power, and her case for justice as the project of social science. Titling her introduction, “Our Raison D’Être,” Cooper first argues that she writes because all standpoints need to be heard in adjudicating conflicts in social life and the debate about race relations and the nature and fate of the Negro cannot yet be concluded:

Attorneys for the plaintiff and attorneys for the defendant, with bungling gaucherie have analyzed and dissected, theorized and synthesized with sublime ignorance or pathetic misapprehension of counsel from the black client. One important witness has not yet been heard from. The summing up of the evidence deposed, and the charge to the jury have been made-but no word from the Black Woman. . . . (i-ii).

Second, as her language above indicates, Cooper’s social theory is based in a quest for justice for the silent and unconsulted “defendant,” here the “black client,” in the ongoing national trial over race relations.

She purposely distinguishes her position from the value neutrality—or “scepticism” —advocated in the positivism of Comte and Spencer, describing her own stance in the “eternal verities . . . The great, the fundamental need of any nation, any race, is for heroism, devotion, sacrifice; and there cannot be heroism, devotion, or sacrifice in a primarily skeptical spirit” (297).

Third, Cooper joins other African American thinkers in laying the groundwork for an American conflict theory that sees the essential dynamic in society as interaction among groups seeking to achieve their own place in the world.

Within this interaction, there will be differences and conflict—what matters are the ways this conflict is carried out and resolved: “There are two kinds of peace in this world. The one produced by suppression, which is the passivity of death; the other brought about by a proper adjustment of living, acting forces.

A nation or an individual may be at peace because all opponents have been killed or crushed; or, nation as well as individual may have found the secret of true harmony in the determination to live and let live” (149). Cooper argues that in suppression, one group has sufficient power to always get its way while in equilibrium groups are balanced enough in power resources that they must interact through compromise.

Cooper describes four major power resources, some standard in sociology, but others, a reconfiguration: material production, ideas, manners, and passion. She is particularly interested in the control of ideas, especially the use and misuse of history and the methodological strategies the oppressed must use to argue their standpoint; the ways manners, especially the manners of segregation, are used to replicate the experience of domination in daily life; and the presence among Anglo Saxons, in particular, of a passion for domination.

Fourth, Cooper offers the pre-eminent evocation of what Collins (1998) will name “intersectionality”; a society patterned by interactions among multiple and unequally empowered groups produces a constant experience in the individual life of vectors of oppression and privilege which Cooper most famously captures in her account of a moment on a railway trip in the South: “And when . . . our train stops at a dilapidated station, . . . ; and when, looking a little more closely, I see two dingy little rooms with, “FOR LADIES” swinging over one and “FOR COLORED PEOPLE” over the other; while wondering under which head I come. . .”(96).

The Washington Context

The experience of living in a segregated society, a society organized by domination, Cooper could have had to some degree anywhere in the United States but Washington, D.C. presented a very particular case, the parameters of which are well summarized by Hutchinson (1881:94):

While the District’s Territorial Government (1871-1874) had passed anti-discrimination laws (not enforced until the 1950s) that outlawed segregation in places of public accommodation, Washington was still a Southern town and displayed attitudes that demanded the separation of the two races. While some wish to believe that women like Anna Cooper, because of culture, educational attainment, or positions in the community, were accorded better treatment than the masses of blacks, such was not the case.

Further Cooper seems to have stood firmly on the principle of not accepting “special favoritism, whether of sex, race, country, or condition.” Thus, one reading of Cooper’s life is that, although lived in Washington, D.C. it did not escape the fate the unnamed narrator’s Southern grandfather assigns to all African Americans in Invisible Man (Ellison 1952) “our life is a war.”

At the same time, and partly as a result of reaction against a hostile white-dominated world, Cooper became part of a close-knit and actively engaged Black community in Washington, D.C.

At a micro level, her own memoirs joyously recall evenings with Francis and Charlotte Forten Grimké and other friends:

“I wish I could find in the English language a word to express the rest, the stimulating, eager sense of pleasurable growth of those days—eight to ten P.M. Fridays regularly at Corcoran Street [the Grimkés] Sundays at “1706” [17th Street, Cooper’s] the same hours” (Cooper [1951]/1998: 310-311).

It was in group life like this that Cooper must have validated her sense of the significance of the group as a place of renewal and confirmation of identity, founded in part in a communal vantage point constituted out of shared experiences of a segregated world.

Washington, D.C. provided Cooper with both concrete examples of injustice in individual lives and access to the national political dialogue around the social practice of injustice. The Voice chapter “Woman versus Indian” is very much a Washington story, despite its wide-ranging subject matter.

Inspired by an 1891 Washington speech by suffragist Anna Howard Shaw that Cooper could either have attended or read of in The Evening Star, it is illustrated in part with stories of discrimination in Washington landmark settings like the Corcoran and its satire of Southern use of “the bloody flag” mirrors the tone and language of the daily press.

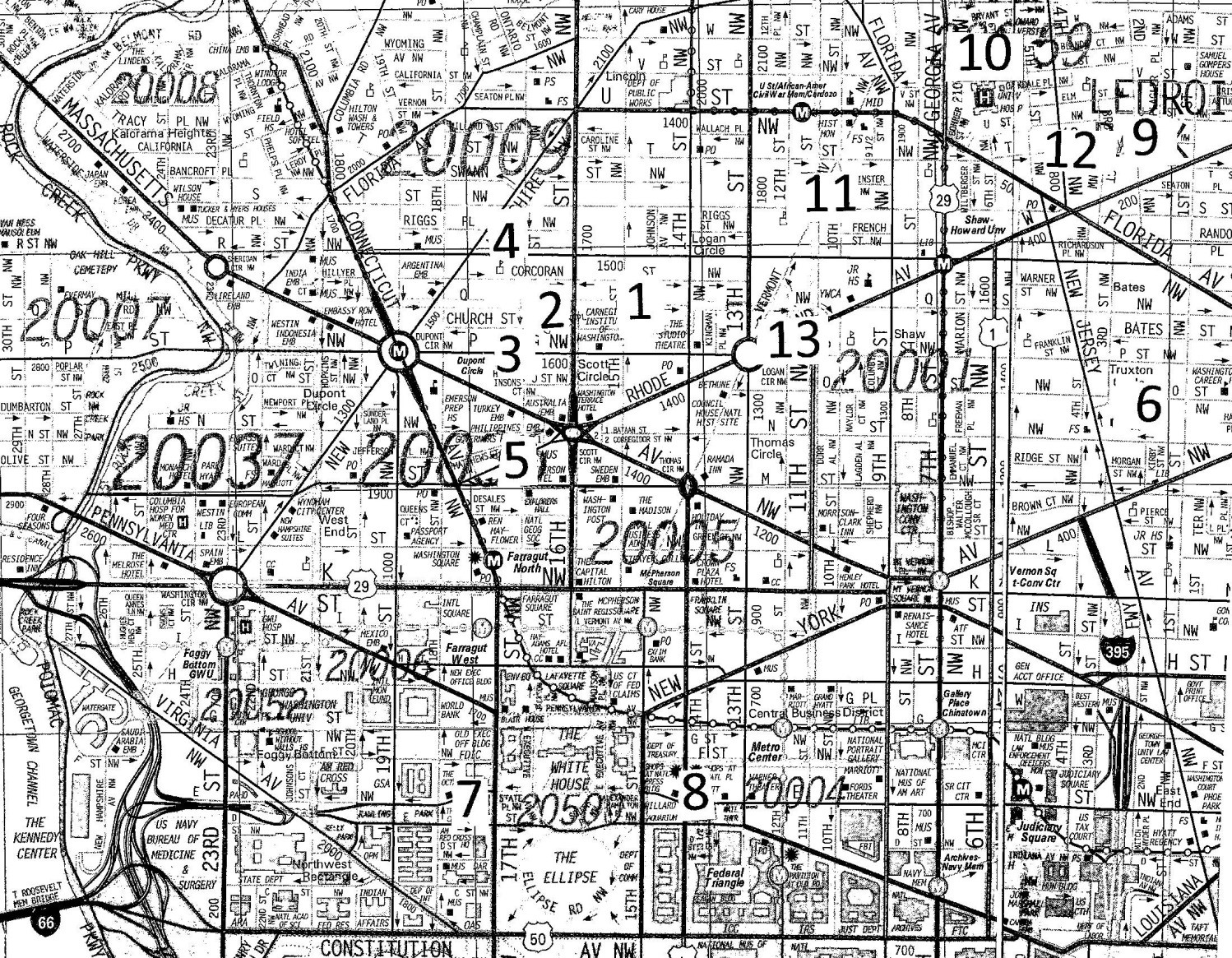

1. St. Luke’s Episcopal, 15th and Church Street. Church of Andrew Crummel with whose family Cooper stayed on first arrival in Washington, D.C. 1887. 2. 1706 17th Street NW. Cooper’s first home in the District, scene of her Sunday evening events with the Grimkés and others. 3. First location of the Colored High School, later the “M” Street School, where Cooper first taught in the District, was located in the Miner Building, named in honor of Myrtilla Miner, abolitionist who worked on behalf of African Americans. 4. The Grimké home 1608 “R”—Cooper refers to it as on “Corcoran.” |

5. The “M” Street School, 17th and “M” Street.

6. Dunbar High School today. 101 “N” Street NW. 7. Corcora Museum, mentioned in “Woman versus Indian” for refusing to admit a black woman who wished to take drawing classes there. 500 17th Street. 8. Albaugh’s Opera House, Pershing Park, site of meetings of National Council of Women and National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1891; unclear if Cooper attended any of these meetings or read reports in local papers. 9. 201 “T” Street—site of Cooper’s final home. |

10. Howard University—Rankin Chapel was site of the conferring of Cooper’s doctorate from the Sorbonne, 1925.

11. Frelinghuysen University main administrative building 1800 Vermont NW. 12. Anna Julia Cooper Circle—2nd and “T” Street NW. 13. Admiral Inn—1640 Rhode Island Avenue— site of organizing meetings for DCSS 1934. |

It concludes with Cooper’s answer to Shaw on the role of women in the race problem:

Why should woman become plaintiff in a suit versus the Indian, or the Negro or any other race or class who have been crushed under the iron heel of Anglo-Saxon power and selfishness? . . . If woman’s own happiness has been ignored or misunderstood in our country’s legislating . . . let her rest her plea, not on Indian inferiority, nor on Negro depravity, but on the obligation of legislators to do for her as they would have others do for them were relations reversed. Let her try to teach her country that every interest in this world is entitled at least to a respectful hearing, that every sentiency is worthy of its own gratification, that a helpless cause should not be trampled down, nor a bruised reed broken . . .(123-124)

Her position at the “M” Street School, as a teacher (1887-1901) and then as principal (1902-1906) put her in the center of the battle between the visions of African American education represented by W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington.

As early as 1892, Cooper wrestled with the problems suggested by this debate. In the Voice chapter “What Are We Worth?” she argues that a solid material base is necessary for any group’s empowerment, the precondition for its collective intellectual achievements: “Wealth must pave the way for learning. Intellect, whether of races or individuals, cannot soar . . . while . . . burdened with ‘what shall we eat, what shall we drink, and wherewithal shall we be clothed.’ Work must first create wealth, and wealth leisure . . . but it is leisure . . ., which must furnish room, opportunity, possibility…”(261).

But despite adhering to this theoretical position, she was not rehired in 1906, a casualty of the bitterness between partisans of W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington and of enmity from her white supervisor, a result of racial tension and bureaucratic in-fighting.

On her return to Washington, D.C. as a teacher, Cooper would help the M Street School’s transition to “Paul Lawrence Dunbar High School” which many credit her with naming and would write the lyrics for what remains to this moment the school’s alma mater.

With no position of real authority after her principalship, with no support save her own earnings as a school teacher, and with foster and adopted children to care for, Cooper nevertheless maintained a life of active community service in Washington, D.C. helping to found and/or maintain the Colored Women’s League, the Colored Social Settlement, the Colored YWCA, the Washington Negro Folklore Society, and the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, Frelinghuysen University, and the Hannah Stanley Opportunity School, in memory of her mother.

Her legacy continues in the District and beyond as an educator, a feminist, and a Black Studies scholar, with a feast day (February 28) in the Episcopal Church, and a passage, the only one by a woman, in the U.S. Passport, a circle in LeDroit Park named after her, a marker on her “T” Street home, and a 1981 Smithsonian Exhibit at the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum.

But still missing is a memorial to her as a social theorist—DCSS has the opportunity to correct this oversight by working for a plaque in Anna Julia Cooper Circle inscribed with passages from her work.

References

Baker-Fletcher, Karen. 1994. A Singing Something: Womanist Reflections on Anna Julia Cooper. New York: Crossroad.

Cooper, Anna Julia. 1892 A Voice from the South by a Black Woman from the South. Xenia, Ohio: Aldine.

Hutchinson, Louise Daniel. 1981 Anna J. Cooper: A Voice from the South. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Lemert, Charles. 1995. Sociology After the Crisis. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Lemert, Charles and Esme Bahn. 1998. The Voice of Anna Julia Cooper. Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield.

Lengermann, Patricia and Gillian Niebrugge.1998/2007 The Women Founders: Sociology and Social Theory, 1830-1930. Long Grove, IL.:Waveland Press.

Washington, Mary Helen. 1988. “Introduction to A Voice from the South by Anna Julia Cooper in the Schomburg Library of Nineteenth-Century Black Women Writers.” New York: Oxford University Press.